I'm walking through tall trees when I see it. Broken branches and leaves crunching underfoot.

Behind me the now familiar batch of buildings that make up Chiapas’ Maya Bell Hotel huddles in a forest clearing. Battered old swimming pool to one side, restaurant and car park the other. And ahead, clearly visible now amidst twisted trunks and undergrowth, is a buried remnant of the ancient world.

A pyramid of the Maya civilization which once ruled these lands well over a thousand years ago.

And not just that, but a platform mound too. It’s well-built masonry long hidden beneath clusters of roots and earth. Then it dawns on me. Perhaps I’m already walking within a plaza of that once mighty urban society. Forlorn now, left to the forest.

I begin scanning the rest of the tree line, suddenly feeling very small. Today the priests, warriors and peasants who once called this place home are all gone, but the evidence they left behind is far from it. Despite decades of continuous digging, countless completely un-excavated suburbs still lie buried beneath the jungle floor. Largely vacant since the fall of the city some twelve hundred years in the past.

Because this isn't just any city. It’s one of the most iconic of all. Integral in the study of Central America’s Mayan Civilisation. Dazzling experts and travellers alike in the midst of the Chiapan rainforest since it was first rediscovered by the modern world just over two hundred years ago.

The night before I’d been woken from my slumber in the early hours. The persistent rain having finally let up for a brief while, howler monkeys could clearly be heard unleashing their cacophonous din across the treetops.

When we'd arrived at Palenque the evening before, after a full days journeying south from Mérida, it had been incredibly wet. The boggy ground already seeming full, despite days more rain on the way. The geography of the place intent on hammering home its difference from the dry north.

For down here in Mexico’s far southern corner of Chiapas, true rainforest is to be found. No longer the dry scrub of the sun-baked Yucatán peninsula of the north.

Down here hills rise and mist-clouds churn ever constantly across the tree tops. Past temple mounds, platforms and scattered settlements. During my visit the rain seemed to very quickly get inside everything, laying a persistent dampen mist upon the inside of my lodge and all my belongings within. But in a place like this it’s very difficult to be disgruntled. Only helped by the monkeys roar, I drifted into a deep slumber that night. Dreaming of ancient priests and distant temples.

I awoke to a re-emergence of the deep rain. A quick breakfast and into the van I shuffled, joining our motley group of travellers from all over the world, and onwards we went, toward the centre of the city. From where fourteen hundred years ago Pacal and his dynasty ruled over one of the foremost kingdoms of the maya world. Amidst the sleepy daydream of an early morning my mind wandered to the masses who once called this place home. Philosophers studying the nature of the universe. Artisans and craftspeople working away at wonders, and above all else, labourers and townspeople going about their business. Oblivious to the machinations and political events of the ruling class.

The several minutes drive from the Mayabell down the highway and into the archaeological park hammers home the enormity of the site, the sprawling map our guide shows us only adding to the sense of colossal scale.

During the Twentieth Century it took decades for archaeologists to survey the place using agonisingly slow ground surveys. And this being a site that is much better known than most. Today, LIDAR technology is completely revolutionising the field. High tech lasers fired from planes finding new structures every season. Even lost cities re-emerging in the deep forest.

The rain lets up just a little as we disembark the bus. Soaked up by massive trunks looming above as we enter the woodland. Serpentine paths winding around river beds and mud-piles. Our guide - El Gato, named for his panther- like eyes he says with a grin, a native of neighbouring Tabasco, soon locates the first stop of the day - a tiny opening under a great tree lined hill side. ‘Who wants to go in?’ he says.

The inside of the opening is surprisingly large. Spacious enough for myself and eventually a Tariq and a Chingis to comfortably walk. And soon we realise - several bats and a whole host of insects to accompany us, a plethora of subterranean denizens having taken up residence in the structure long ago. It had been above ground once. A stone built house for well-to-do members of a Palenque community. Subsumed under the forest floor by generations of falling vegetation.

What had life been like for the people who lived here I wonder as we head further through the canopy. Did they have any sense of the political and military events so often talked about by Mayanists today?

Several more underground houses later we arrive at an overgrown temple crowning a rising hill-top. Up and up we climb past mud piles and squelching puddles, clinging to vines as we go.

Only then it dawns on me that we’re climbing a pyramid, a big one. Completely covered now by diagonal forest floor. Only the top most building peaking out at the summit gives away the reality of its man-made nature. A hint of what almost all Mayan cities looked like at the dawn of the Nineteenth Century before they were cleared by archaeologists.

It remains an amazing fact that despite Palenque being one of the earliest cities re-discovered by modern excavators, it still has near unfathomable mysteries left to be unlocked. Only the very immediate centre having been properly cleared and studied, and that’s where we're headed next.

Our first glimpse of the city centre is of grey-black limestone stairways rising endlessly to the sky. Temples and wood-supported platforms sprawling upwards through the trees. And when we exit the shelter of the woodland toward open green fields, sodden feet our companions, the sight we see isn’t too dissimilar to that which would've greeted Mayan pilgrim travellers some thirteen hundred years ago when the city stood at the very height of its prime.

The intense reds and whites of the stuccoed facades have long gone, but the immensity of the architecture remains. The sheer shock factor when faced with such colossal constructions. Built by human hands alone, no pack animals existing in this part of the world. But as far as most Mayans were concerned, those mighty edifices could only have been the work of gods.

Adjacent to that first massive pyramidal complex I soon spot the most famous structure of the whole site, and one of the most famous in the entire Maya world. The Temple of the Inscriptions.

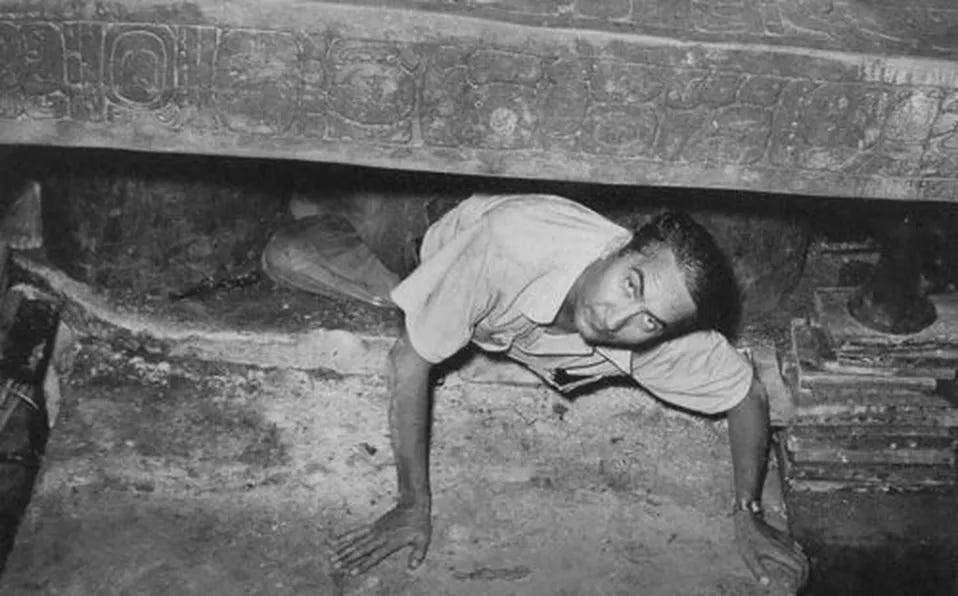

It was here in the 1950’s that Mexican archaeologist Alberto Ruz Lhuillier worked with his team for more than ten consecutive seasons. Uncovering vast amounts of information on the history and society of the kingdom. Most famous of all however was their digging under that particular pyramid structure. For here was excavated the very first tomb ever discovered in the Maya world, and one of the first in the Americas as a whole. The excavations revealed vast amounts about Maya beliefs on life, death and society in general. Before that day, Maya funerary customs had been a total mystery.

Within the tomb, coated in jade - one of the most precious materials in the Maya world, the body of King Pacal the Great was found. You might know him from the Civilization series of PC games as the perennial leader of the Maya faction. Fated to be the first uncovered during the modern age, quite simply, unlike almost all other Maya kings & queens, he’s famous.

But Pacal’s legacy is a strange one. When infamous Swiss pseudo-intellectual Erich von Däniken published the best-selling ‘Chariots of the Gods?’ In 1968, he argued Pacal’s sarcophagus lid to be a depiction of an ancient astronaut. Though erroneously claiming it to have been found at the city of Copan many hundreds of miles away in Honduras, the details and the facts weren’t important. The Pseudo-archaeological concept of Ancient Aliens was born.

When travelling across the far north of the Yucatán a week earlier I’d spent a day with a German guide advertising himself as an archaeological expert with some equally interesting views. ‘The Smithsonian has several giant skeletons they keep hidden away’ he tells me, as well as a bizarre hypothesis about an Egyptian Old Kingdom city of 50,000 inhabitants nestled in the deep recesses of the Grand Canyon.

Thankfully we arrive at the city of Ek Balam just before my brain melts out of my ears, and by the time we explore Coba’s tree-lined highways I’m not at all surprised when he begins his Ancient Aliens spiel.

Amidst this slew of bizarre claims Wolfgang (name changed to protect his identity) relates a particularly grisly incident when every archaeologist working on The Temple of the Inscriptions in the 1950s dropped dead upon opening Pacal’s tomb. Unfortunately for my confused guide, it takes just a few seconds google to confirm Alberto Ruz Lhuillier lived happily until 1979.

Another of his uncorroborated claims is of another tomb at Palenque, that of The Red Queen. Coated, he says, in a mysterious red substance unknown to science. At Palenque it is very easy to find the name of that substance. Cinnabar.

In the face of these bizarre and easily refutable claims I realise just how fragile all this knowledge really is, and how easily it can crumble in the wake of charlatans.

Upon hearing of my travel plans Wolfgang also unreliably told me of Chiapas being an incredibly dangerous place, and that I’d certainly need a police escort.

We do head past Zapatista villages. Autonomous Mayan communities who’d gone their own way since the 1990s amidst armed conflict. Quite justifiably having rejected governorship by the far off central Mexican government after centuries of foreign rule. Though today the place seems incredibly calm. The people friendly & welcoming. In my opinion a much calmer place than the bustling chaos of cartel-ran Playa Del Carmen where Wolfgang calls home. It’s a reminder that perhaps we shouldn’t listen to the media machine so much.

The media often spins a particular story, and story is ultimately how we view the world. Go and see a distant land for yourself and the picture on the ground is often very different.

We spend the rest of the afternoon exploring the city. Past aqueducts, ball- courts, endless temples, pyramids and buildings. Palenque is a stunning place, nestled within an incredible natural landscape. It’s one of my favourite Maya sites of the whole trip. And when finally we get back to the hotel, after a brief swim in the pool, I know what I have to do. Overgrown pyramids and temples looming all around.

If you want to hear more about the Mayans then head on over to my YouTube channel for a four and a half hour deep dive into the entire history of the Maya, from the distant Second Millennium BC to today, including a colourful cast of kings, queens, conquistadors, explorers and archaeologists. Cheers and see you next time.