In the wilds of southern Greece olive groves crowd on pebble-strewn earth. Artefacts and masonry of all eras nestled among the brambles and the orchards.

Alongside scrap metal and plastic, like few other places in the world this region of the Mediterranean has a glut of evidence from the ancient world too. Not just settlement sites and outposts but vast metropolises of the ancestors in abundance. A time when many of those settlements of antiquity surpassed modern towns in both size and relative splendour.

One of those places, hidden up high on a little visited ridge-line in the south central Peloponnese is Nichoria.

Unlike so many others in a wide arc from here all the way to the north side of the Black Sea, and westwards too to Italy, this sprawling site doesn’t originate in the Archaic or Classical eras of Greek history. Of Athens & Sparta & Alexander the Great.

Nichoria dates to a time before. To the First Greece. For here are to be found a number of Tholos Tombs, relics from the Mycenaean Age. Of Homer’s Odyssey and Jason’s monster ridden search for the Golden Fleece. Of forlorn colossal citadels of the prehistoric world. Cyclopean masonry and heavily armoured chariot riding warrior lords. Of elaborate palaces and intricately crafted bath tubs, olive oil, feasting and wine.

Though little remains now above ground from that ancient time, to walk in the once mighty citadel here at Nichoria today is to gain a fleeting window into the heroic past.

I - Search For A City

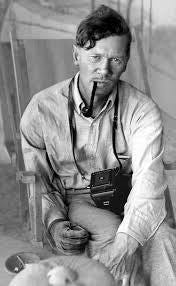

When archaeologist Carl Blegen set about digging up the ancient ruins of Pylos In 1939 the world watched on in awe. Within weeks, astounding discoveries were made.

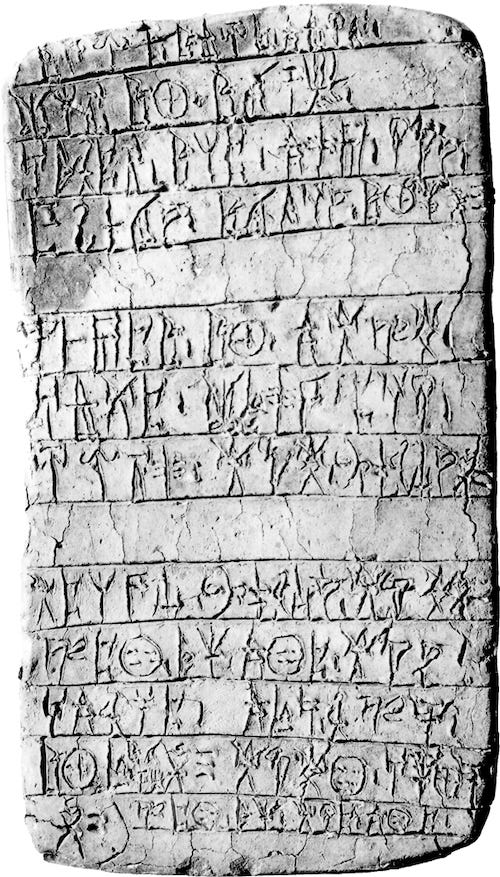

In the midst of an immensely impressive palatial complex dating to the Second Millenium BC an entire archive of records was unearthed, written in a mysterious text known as Linear B. By far the largest collection of the writing system ever discovered, it could only have been the long lost library of an ancient European kingdom, known previously only in epic storytelling tradition and myth.

Soon enough the place was named for the wise king said to have ruled these parts in the days of the Trojan War. The long disappeared world of the Iliad and The Odyssey seeming to come back to life. Today, whether strictly historical or not, it still proudly bears that name. The Palace of Nestor.

Though a golden age for archaeological research, the late 1930s was of course a time of immense societal turbulence and cataclysmic change too. Within a matter of months of the first digs at Pylos the Axis powers moved their plans to fruition. Greece, falling within the orbit of fascist Italy, would doggedly fight for its independence for years to come.

When Blegen was finally was able to return to Pylos to regroup with his Greek colleagues; like the aftermath of all wars, everything had changed.

For one thing; radiocarbon dating, a by-product of the ridiculously high budgets pumped into the war effort, was bringing archaeology in line with modern science for the first time. Providing exact dates within around 50 years or so where rough estimates had sufficed before. But when it came to periods of the very late prehistoric period, such as the heyday of Mycenaean Greece and the previously only mythic Trojan War, the new dates were often shockingly accurate to the estimations of classical scholars.

Unknown to Blegen, on the other side of the Atlantic, a New York scholar had been tirelessly working for decades on the Linear B tablets found on Crete as far back as the late 1800s by Sir Arthur Evans.

Though Alice Kober died before the work could fully be brought to fruition, her efforts and those of countless others would culminate in 1952 when Linear B was finally successfully translated.

As it so often does, the breakthrough came from an outsider.

Michael Ventris, an amateur code-breaker had long had a hunch that Linear B was in fact Greek, in its very earliest archaic form, and that hunch turned out to be correct.

Finally by the mid 1950s for the first time in over three thousand years the words of that ancient land could be read. The stories they told, though usually consisting of minimal records rather than epic sagas, have nevertheless added near unfathomable amounts to our understanding of Bronze Age Greece. Specifically revealing unique insights into the inner workings of one of its foremost kingdoms, sprawling across Messenia. In Homeric tradition, said to be the kingdom of Pylos ruled over by wise old Nestor.

Amidst the hundreds of tablets in the so called ‘Archives Complex’ at the Palace of Nestor were found a number now known as the Coastguard Tablets. A unique list of the defences and settlements in the kingdom, for administrative purposes described as divided into two provinces - de-we-ro-ai-ko-da-I-ja and pe-rai-ko-ra-I-ja, meaning the ‘Hither’ and the ‘Far’ Lands. Usually assumed to be oriented from Pylos, perhaps as well as the recently discovered secondary capital centre at Iklaina not far away.

The list begins at the northern portion of the ‘hither’, or ‘near’ province, running down and along the coast of the peninsula, ending with just one town in the ‘far’ province. It is possible that the only settlements listed are those on the coast or near enough to the coast to act as part of a sea borne defence system. Perhaps explaining why most of the settlements in Pylos, unlike the Argolid and elsewhere, did not need fortification walls, their mastery over the coast being their defence.

Though no consensus exists today, given the fragmentary nature of the sources and the sheer antiquity of their age, the Hither or Near Province has nonetheless been widely hypothesised to lie west of the Aegaleon and Skala mountains, with the Far Province and its shorter coastline situated within the hinterlands of the Messenian Valley. Just one town of the Far province is named in the Coastguard Tablets. Not surprisingly ever since their translation scholars have hypothesised where that town could be.

Translated as the rather indecipherable name Ti-mi-to-a-ke-e, it was not the capital but one of seven principle towns, usually assumed to be a coastal site or near to the ancient shoreline at least, as well as being close to the provincial border. With hopes of finding another archive, the search was on.

Of the nearly two hundred sites surveyed over the ensuing decades, just a handful of particularly large candidates were pinpointed as potential locations for Mycenaean towns or cities. One of those sites, among the ten largest in the whole of Messenia and a place already highlighted by Ventris’ colleague and Mycenaean expert John Chadwick, is Nichoria.

Besides the Taygetos mountains rising in the haze to the east, the summit of Nichoria provides excellent visibility in all directions. A natural crossroads well placed for communication as well as defence.

Only two kilometres south is the Messenian Gulf, just about visible today in a narrow coastal strip past hilly expanse of olive groves. It is important to remember that shorelines shift and change over thousands of years. Here in ancient days the waves would’ve lapped much closer than they do today.

In the Pylos Tablets Ti-mi-to-a-ke-e is said to have acted as a lookout station. One node in a vast coastal network.

We can imagine runners heading off or beacons being lit to send messages to the palace as soon as unwanted visitors were seen, be they trade ships to be taxed or plundered, attack fron other Mycenaean palace lords or pirates.

A little further north on the adjacent hill prehistoric remains have been found too, tentatively identified as a lookout post for the city. Perhaps to protect the exposed posterior side from surprise visits.

With hopes of archives and immense discoveries the archaeologists soon moved in.

II - Expedition Messenia

The archaeologists knew it was special as soon as they saw it poking out of the ground. Deep hollow eyes staring back at them from the sundered earth. Not much wider than pin pricks when compared with some of the more famous finds of its kind like the lady of Phylakopi and the multitudes of idols found at Mycenae. And yet; crude as it is, somehow primal, fearsome even, the so called Dame of Nichoria does seem to reside within that well known category of Mycenaean sculpture, most famously seen with the so called idols of Mycenae itself. At just 0.067m high it is a small piece, the lower part of the face unfortunately having been chipped away at some point in the past, leaving behind mystery of what the face originally looked like - whether it had been round or long and pointed like the Lord of Asine.

From the polos the Dame wears it has been concluded to be female, perhaps like hypothesised examples from Minoan Crete, representing a cultic priestess. When the piece was first sculpted it may well have been up to an impressive third of a metre in height. Though no evidence of paint has so far been found, its gritty and coarse surface may simply have worn away over the millennia.

Today the Dame of Nichoria remains one of the most interesting pieces found at the site. Speaking of a very real apogee of Mycenaean occupation that took place here in the Late Helladic III B Period, aka the 13th Millenium BC.

By the time the intensive five year programming of large scale digging undertaken by the university of Minnesota under the direction of professor William A McDonald was completed in 1974, a number of fascinating breakthroughs had been made. Thankfully for the archaeologists involved, Nichoria had indeed been a place of great significance. Though, given the complicated layers of habitation, and significant levels of erosion and damage over the millennia, the place remained frustratingly difficult to comprehend.

From their first arrival in 1969, to the last trenches of 1974, a total area of 50,000 square metres would be dug. Six strenuous campaigns of trench digging meticulously covering an area of 5000 square metres. And yet though this may sound a lot it represented just ten percent of the areas showing evidence of human habitation. As with all digs, priorities had to be made. Choices taken.

In addition to the various pieces of Nichoria that were still privately owned and thus out of bounds for digging, only some of the trenches made it down to undisturbed soil, both due to time constraints and as a result of the decision to not destroy later buildings to get down to the ever mysterious Mycenaean levels.

Nevertheless, even with these difficulties, the Mycenaean pottery pieces alone numbered over eight hundred; small finds in general more than two thousand. Animal bones and sculpture fragments in particular giving significant insights into burial customs, diet, architecture and even foreign contacts. Above all else seeking evidence of Nichoria’s relationship with the rest of the Pylos kingdom, one of the more significant finds was the evidence of resident bronze smiths, like the Dame, dated by pottery fragments to the era of the tablets (LHIIIB).

By the 70s, though John Chadwick had ultimately changed his mind on Nichoria, surmising it to be not Ti-mi-to-a-ke-e after all, but potentially another town, in the south west quadrant of the near province, the importance of the place as a Pylian town matching descriptions in the tablets could not be denied. Crucially all being described as having bronze industries tied to the palace, with contributions being passed back and forth. The bronze working at Nichoria then provides a rare convergence of contemporary Mycenaean records and archaeology.

—

Back in 1969 it had all begun when a test trench in the north and west of the site revealed Mycenaean foundations and a great sigh of relief. Though like most areas of the site, which continued to be intensively inhabited until well into the high medieval era, later ruins stood on top, obscuring much of the most ancient levels. In this case, mysterious geometric structures from the end of the dark age following the Mycenaean age.

And yet even so, entire streets from that late Bronze Age city were ultimately uncovered, especially on its southern side where curving terrace walls gave tantalising hints to the majesty of the place in ancient days.

On that southern side, running along and over the edge of the hill, another wall was found, (running north east to west south-west), which may also be of Mycenaean date. Though this particularly intriguing section was unable to be excavated fully it has been hypothesised to house the deeply buried remnants of a grand gated entranceway, perhaps not worlds away from the famous examples at Mycenae and Tiryns.

On the western side, in a section known as Area V, a number of important finds were made. In that part of the hill, thought to have once formed a natural gully or hollow, centuries of plowing and vine farming had unfortunately caused severe destruction. Nevertheless a great deal of material was uncovered, including corner moles for creating intricate jewellery of interlocking ivy leaf bands, and the Dame of Nichoria.

In addition to the bronze working area in Unit III-IV actual bronze goods and other crafted items were found too. For example well over two hundred spindle whorls were collected, dating all the way from the Middle Helladic to the so called dark age following Mycenaean times. Notably, on a rubbish dump one large figurine body dating to the early days of Mycenaean settlement was found, the head unfortunately missing. (N1528)

Though animal figurines are fairly common at Mycenaean sites. Generally assumed to be idols, perhaps representing deities, larger ones are much more rarely found. Notably, a sizeable fragment of an animal figurine was found at Nichoria, thought to be a pig.

Originally standing at around 0.10 metres up to its neck, larger when it had a head, it’s not the most impressive example ever found, but it does put Nichoria within the mainstream of late bronze age society at the time. Not far away was also found a small horses head not unlike those found at Mycenae and published by Angela Tamvaki.

And yet for those searching for the lost city of the archival records a single pot sherd provided the most tantalising evidence of all, suggesting the existence of a literary elite, for it bore an inscription in Linear B.

But what of the layout of the settlement? Where did the people live? And what can the archaeology tell us about their lives? Well, unfortunately the area has suffered so much from erosion and looting over the years that stratified information is patchy at best. Rather than a detailed plan we have an immensely complicated series of habitations obscuring Mycenaean foundations.

But when those buildings can be seen, they are a far cry from the glittering palatial centres at the heart of the Pylos polity. In comparison to the palace of Nestor and the multi storied complex at Iklaina, they have been called crude and provincial.

The final reports from the Minnesota expedition for example stated with certainty that no building prior to the Byzantine era had been roofed with terracotta tiles. A luxury style that had been seen as early as the Third Millennium BC at sites like Lerna in the more affluent Argolid.

Nichoria did not seem to follow the conventions of the more distant capitals. Perhaps the elites here simply didn’t need to invest their wealth in such flamboyant displays of power, towering over the surrounding hill and plains people outside their walls anyway.

But what of that elite? As usual, for them we have some of the best evidence of all. Seen most obviously in the mighty dromos and tholos tombs that survive largely intact to the present. One in particular at Nichoria, intricately built from limestone likely to be used by the ruling dynasty, ranks among the largest and most impressive in all the Mycenaean world.

When cleared in 1971 and fully excavated down to its original base level in the next year, as expected, most of the tombs contents were long gone. Various fragments of ivory and bronze and sherds just giving hints of what had once been interred. The one constant in archaeology often being near total disappearance to oblivion.

Far from a modern occurrence, the initial opening and looting of the tombs took place as early as the end of the Mycenaean era.

By the 4th century BC they had become places of veneration once more, just as they likely were at the time of their construction, places to visit the venerated ancestors, real or imagined. Clearly still prominent structures, like many other tholos and chambered tombs in Messenia, becoming cultic centres.

Elsewhere in the site a great deal of so called ‘dark age’ evidence dated tentatively to around 1050-975 BC is regularly found among the scree and rubble, including coiled bronze rings, earrings and an elaborate pin. A good deal more evidence than at many Mycenaean sites, suggesting some sort of continued habitation. The possibility of a collapse here like at the palatial centres has been suggested by possible burning evidence, though this is far from definitive.

What the evidence does definitively show is that after the so called ‘dark age’ came the geometric period, equally mysterious time before even Archaic Greece. During that time a much reduced Iron Age village would develop in the section of the site known as Area IV

Given the evidence from the digs. From the cemeteries, the buildings and material goods, there is no question of the re-use of the Acropolis in the era after the Mycenaean apogee. Often in a much reduced state. After about the 11th C BC, perhaps after an intermission of 100 years though we cant say for sure.

But what of the beginning of Nichoria? How did it develop? And how did it become part of the Pylos kingdom?

III - From Polis to Provincial Capital?

When people first came to Nichoria, long before the fences and the cultivated olive groves, it looked very different to today.

When those early farmer ancestors of the late Stone Age arrived, the place was still a prominent feature or course, though not yet shaped by the hands of humanity. Portions of the cliffs edge and hillside ultimately having been cut down and moulded over the ages.

Forests coated the land in those days; of gnarled oak, pistachio and more, and though largely invisible now from an archeological perspective, high places provided good vantage points for settlements. But most alien of all, visible in geological features indicative of coastal erosion on the base of the cliffs, the sea likely lapped at the hills edge.

Only in relatively recent centuries would the sandy coastal plain we see today begin to form. So when the revolutionary concept of metalworking first appeared in Greece at the beginning of the third millenium BC, seeming to go hand in hand with elites since the very beginning, coastal trading routes became integral to the power of rulers in the increasingly socially stratified society of the Bronze Age. Nichoria, with its ready made defences and adjacency to the sea roads, must have seemed a perfect location, and unsurprisingly a small autonomous community began to coalesce.

Archaeologist Philip Rapp goes so far as to suggest an archaic lagoon once extended well into the valley mouth of the Karys River, providing not just shelter form storms but good landing sites for small prehistoric vessels, until it dried up in the Roman era. The precise location of the harbour at Nichoria however remains a mystery. No digs as of yet having confirmed a location in the ever changing landscape.

Given the apparent coastal nature of the site, it comes as little surprise then that some of the most impressive remains from the early layers seem to have originated, at least in influence, from elsewhere. For in the later part of the Middle Helladic Phase, in terms of pottery styles, there is a great deal of similarity with Minoan Crete. That famed island of palace builders and seafarers spoken of by the classical historian Thucydides as the first great sea power, or thalasocracy of the Aegean, lying not far to the south. In myth ruled over by King Minos, the builder of the labyrinth; archaeology too suggests a very real flourishing in the middle Bronze Age. Likely influenced a great deal by the power of Ancient Egypt, they in turn likely had a marked effect on the people to their north and west, along shore lines as far north as Troy.

In those days the archaeology at Nichoria suggests a modest scattering of families scattered widely over the ridge, a largely self contained community with evidence of metallurgy. And though cultural influence from Crete can be seen, no doubt trade links foestered with one or more of the palatial centres of the island, no evidence of political or economic domination can be seen. No burials are found either, which matches with Crete itself for that period, sky burials or sea burials hypothesised as means of disposing of dead, suggesting the culture of Crete may have been somewhat contagious.

With the exception of Malthi, Nichoria remains one of the only prehistoric settlements in the South-Western Peloponnese to be investigated in depth. The two local centres seeming to have played similar roles throughout the Middle and Late Helladic Periods, ultimately sharing the same fate of the wider political events of the Aegean. For by the Sixteenth Millenia BCE major change was on the way.

In around 1600 BCE the island of Santorini exploded, obliterating habitation on the island and launching tidal waves and dust clouds across the sea. Such was the power of the destruction and resulting tidal waves, the pumice from the eruption can actually be seen at Nichoria. Much closer to the eruption zone however was Crete. A century of chaos ensued and the forging of an entirely new system.

To the north meanwhile, in the Argolid of mainland Greece and neighbouring Attica and Boeotia, in bays and inlets sheltered from the shockwave from Thera, the various ships and war vessels of the mainland, previously a rather provincial culture would move out and forge the world anew. Soon enough, Crete and the rest of the Aegean would be Mycenaean.

Nichoria was no exception; like a history of the Mycenaean world in miniature, a gradual shift being visible in the archaeology as well as significant population growth. The place seeming to be the centre of an emerging political and social unit of considerable complexity in the Late Helladic I and II, very much in the mainstream of the Mycenaean world. One of the main pieces of evidence for this, is from the cemeteries, dating to the very earliest days of the late Helladic, continuing in throughout the Mycenaean age. For unlike the previous eras, the great lords and ladies of Nichoria were now laid to rest in mighty tombs that are still visible today.

Throughout the last two hundred years of scholarship on the Mycenaean world, ever since the halcyon days of Schliemann and Tsountas, a great deal of emphasis has been placed on tholos and dromos tombs as concrete evidence of so-called ‘royal’ dynasties. After all, those early researchers reasoned, who else but kings and queens could afford such edifices?

And yet, in reality, besides the immensely wealthy grave goods compared to other graves of the time, outside of Homer’s Catalogue of Ships which talks at length of petty kingdoms though actually written down hundreds of years later, very little corroborating evidence exists. The massive tomb on Mykonos for example - now languishing as a rubbish dump for an oblivious hotel - though once the greatest in all the Cyclades, does not seem to correspond with a nearby city or centre of any known kingdom. Likewise we do not in actuality know whether the early so called ‘kings and queens’ of Nichoria actually controlled the surrounding territories or even villages lying much beyond the orbit of the settlement in their most prosperous phase when the tombs began to be in use. It begs the question whether these were actually royal dynasties at all, or if a multitude of ways of governing could have been in use, like proto-polises of the later classical age.

Though it seems likely that exploitation of land resources in the immediate areas would have been intensive, along with considerable trade coming and going by land and sea, without written records it remains difficult to know whether a polity existed solely on the acropolis itself or extended to the surrounding area. Though clues can be gained from neighbouring sites.

—

Just two and a half kilometres away at the village of Daphni, another tholos tomb is to be found, along with possible indications of an adjacent Mycenaean settlement. Should we be imagining a fully autonomous neighbouring dynasty within three kilometres of Nichoria? Or should alternate hypotheses be sought for Tholos tombs? A cadet branch perhaps, like those that have been suggested for Tiryns, Midea and Mycenae itself, or even a ruling family of favourite courtiers designated as princes to supervise villages and towns. Not quite fully independent politically, but following burial customs of the capital as best they could.

And finally we have the question of just when, how and even if, Nichoria was subsumed into the larger Pylos polity.

What we do know is that by the Fourteenth Century BCE, the apogee of the site was ushered in. The quality and quantity of the finds from the Tholos tomb, even with the place having been looted show prosperity reached a peak. Whether the rulers interred there were put in place by Pylos or not, lasting into the Thirteenth Century BCE apparently without a break, we can’t say.

As for the ‘palace’ hoped for by the archaeologists; though nothing concrete has been found thus far, during the LHIIIA period there are indications that something akin to one may have once existed. In the central saddle of the south- eastern side of the ridge, in the location known as Area IV, a heavily eroded LHIII complex has been suggested as the administrative centre of the site. Perhaps once independent; later ruled over by a provincial governor reporting back to Pylos.

Just like it says in the Iliad then, the possibility exists of a dynasty of vassal kings ruled by an over-king; themselves in turn ruling over even smaller units. Though whether this distinction was one that even mattered to most inhabitants we can’t say, life possibly going on much as it had before.

And as for the governor of the city, amazingly, if the place was indeed Ti-mi-to-a-ke-e, the coastguard tablets give us his name.

IV - The Life Of Perimos

When I visited Nichoria in the late summer of 2022 a great deal had changed since the days of the Minnesota expedition; those excavators unknowingly having stood near the end of the so-called ‘golden age’ of archaeology. For want of funding and inclination, large-scale excavations of sites like this one are rare now. Reinterpretation of existing information and small scale digs having become the norm.

For many reasons, to visit today is to step back in time. And though a few individuals did come through during our brief time on the ridge, far from the usual hordes of tourists filling the major sites like Mycenae and Athens, we mostly had the place to ourselves. There is no entrance fee; no visitors centre, and no gift shop. Few fences to block off out of bounds areas. And for precisely these reasons visiting Nichoria was one of the most memorable experiences of the entire trip.

So it was then, on a sleepy morning on the road from Nafplion to Pylos, we made our stop. As far as I could tell some fifty years had passed since the place had been dug. The still visible trenches and exposed foundations having become overgrown over the years. Dangerous even, to unsuspecting passersby.

With few information boards and only scattered fragments to be found online, sites like these demand an imagination. Besides the Tholos tombs there are few visible remnants. But that’s precisely why I love the place. For someone used to British hill forts, and Neolithic settlements, imagination is often all we have. Cyclopean wall, or ridge line. Ancient citadel or patch of earth, it isn’t easy to tell. But in order to do so, thankfully we can turn to the records of the digs themselves.

And in the late 60s when the team from Minnesota began digging here, almost immediately they found the place to have been a flourishing settlement. Though as we have already seen, one of their great desires remained to find an archive of Linear B tablets like those found at Pylos dating to the LHIIIB2 period, the late Thirteenth century BCE.

Tablets that document an extensive and well organised bureaucratic system. A snapshot of a kingdom stretching north to the Nedha River and along the coast to Kalamata, indisputably administered from the palace at Pylos; fired, fused and saved from oblivion entirely unintentionally when the place was destroyed around 1200 BCE.

Unfortunately after some forty weeks of systematic digging, no archive was found. Nor even a conclusive palatial centre or administrative hub. A mere single pot sherd bearing a possible mark of Linear B being the only evidence that anyone at Nichoria had been literate at all.

Nevertheless, when utilising the Pylos tablets alongside the archeological data we can glean a great deal of information not only on how Nichoria functioned but how it was likely to have been governed too, even if its identification as Ti-mi-to-a-ke-e is incorrect.

For the tablets give the mayor of Ti-mi-to-a-ke-e at the time of the destruction of Pylos a name. An extremely rare figure coming alive from those ancient records. His name was Perimos. And even if Nichoria was a different site, surely it too had a Perimos.

What happened to Perimos, or whatever the mayor of Nichoria had been called at the time of the end of the kingdom remains completely unknown. As does the manner of its destruction and who precisely carried it out, the violent upheavals at the end of the Bronze Age remaining one of the great mysteries in world history. With outside invasion and domestic revolution being equally suggested. It’s even possible that our mayor was one of the leaders of the attack on Nestors Palace, throwing off the shackles of distant rule in a time of change. For Nichoria may well have survived the end of the bronze age. At least for a time.

But what of Perimos before that fateful destruction? And what can the tablets tell us of Nichoria at the very apogee before the fall?

Up until the cataclysmic change that brought the palatial centres of the Aegean to their knees by the Twelfth Century BCE the resource that

kept the world moving was bronze. In that time before currency as we would recognise it, and when the vast majority of people had no access to metal of any kind, that alloy of tin and copper was utilised primary to forge instruments of power. Weapons of war; beautiful craft items and gifts of kings.

While copper was rare, being found only in a handful of locations, tin was virtually non-existent, those who could gain access to the meagre trickle coming in from what is now Afghanistan and perhaps a few other places, could become extravagantly rich. And though we don’t know enough about Bronze Age trade to definitively talk of monopolies, it does seem that in the Aegean the tin trade was linked above all else with the central authorities of the palatial centres.

In Messenia in particular the Pylos Tablets speak of bronze imports being allocated to each town and regional capital in melted down lump sums, to then be reworked by the various regional metal-smiths as they saw fit. Fascinatingly, at Nichoria, chemical analysis does indeed suggest most of the metalwork to have originated from reworked bronze rather than alloys of raw tin and copper.

Chemical analysis also indicates the bronze to be extremely low in tin; perhaps the rarest and most sought after resource in the world at the time, and one clearly not given up lightly by the kings at Pylos. The bronze at Nichoria is so low in tin in fact that it almost can’t be called tin bronze.

And of course in return for that bronze that marked the elite at Nichoria out as different, such regional towns no doubt provided a range of services for the palace centre at Pylos. In return for protection no doubt they paid their taxes, and in a pre-monetary system this came in the form of goods and when the need arose, military service. Indeed, the very reason why the concept of literacy was forged in the first place was to record such transactions and tributes. And Linear B is no exception. The surviving tablets mostly recording economic information. And within the Pylos tablets in particular we are told of the productivity of the various settlements of the kingdom.

No doubt due to the capital brought in for their lucrative woollen coats, sheep were by far the most common animal recorded on the tablets. Other animals recorded on the tablets are pig and a few cows, used primarily for their hides. Though in the archaeological record cattle are extremely rare. Goats too, not mentioned in the tablets, are the common of all, used primarily for their milk and meat as sustenance rather than exporting to the palace.

Besides animal produce, among the other goods of the utmost importance to the palace economy was flax. Nichoria, sited on one of the most heavily watered places in an exceptionally fertile province, with no fewer than five major rivers, and broad coastal plains, was perfect for the growing of the product. Today the region still produces half of the flax grown in Greece. With a convenient land route also existing to the Pylos heartlands to the west where raw flax could be sent on to the palace, in return for his aid in bringing tribute to his overlord Perimos was likely a very rich man. And if the Tholos Tomb did indeed contain the remains of the leaders of the site, the bone and skull fragments of between ten and seventeen individuals having been found in all, Perimos may well have been laid to rest among them. Tiny fragments left behind by grave robbers giving hints of the bronze vessels, sealstones and other riches deposited with them for the next world.

Artefacts that clearly place Nichoria very much in the mainstream of Mycenaean society. Far from a backwater as once assumed, pottery fragments too demonstrate a few imports form the Argolid, and even Mycenae itself. And in one particularly well preserved area the buildings line up neatly along the remains of a well-planned cobbled stone street.

So then, though we may have discovered where Perimos’ life came to end, and there is of course no reason to assume that a palatial complex would even be recognisable here in the same way as they are at Pylos, Tiryns, Mycenae or Thebes, one last question remains. Where did our governor reside in life?

At both edges of the ridge slightly raised up areas, acropolises within the acropolis; have long been hypothesised as potential locations for the administrative heart of the city; homes of the rulers of Nichoria, or even a lost palace.

One of the sides, though damaged extensively over the millennia, revealed no evidence of Bronze Age habitation at all. The north-west edge however, though also having suffered extensive damage over the millennia, did reveal evidence of Mycenaean buildings. Only fragments having survived.

If an administrative archive had ever existed here, without clear evidence of a conflagration at the end of Nichoria’s Bronze Age, the sun-dried tablets would have simply been scattered and disintegrated back to the earth. Paradoxically, it is only destruction that saves such records from oblivion.

Today Nichoria lies dormant, awaiting further techniques in the future to unlock the last of its secrets. Thankfully, it is safe, for now.

Thanks for reading. I’m Pete Kelly. If you enjoyed this article then you’ll likely enjoy this video I made on another Bronze Age culture. Until next time.

Pete, I'd love to write about Linear B soon! Would it be okay if I quoted your post a bit in mine? I love your way of explaining this history.

Great job, loved the video on YouTube. My family is from close by, I would love to see more videos about the area.