At the heart of the Cyclades stands a beach like no other.

Loomed over by mighty mountain chains, the island of which it is a part, Naxos, is unique in many ways. To enter the hinterlands of this largest landmass in the Cycladic Islands is to roam in a continent in itself. A land awash with mythic associations and genuine epoch defining archaeology. Where the demi-god Dionysus danced and Zeus himself is said to have spent his childhood.

Much closer to the sea, past the foothills and ancient groves of the western lowlands, the remains of Mycenaean chamber tombs sprawl at the waters edge. Mostly ruined now on the jagged rocks of Aplomata where they’ve stood for well over three thousand years. Victim to the earthquakes which have so often blighted this hauntingly beautiful land.

The tombs overlook a modern town today, commercial hub and largest on the island. A new shoreline for a new epoch.

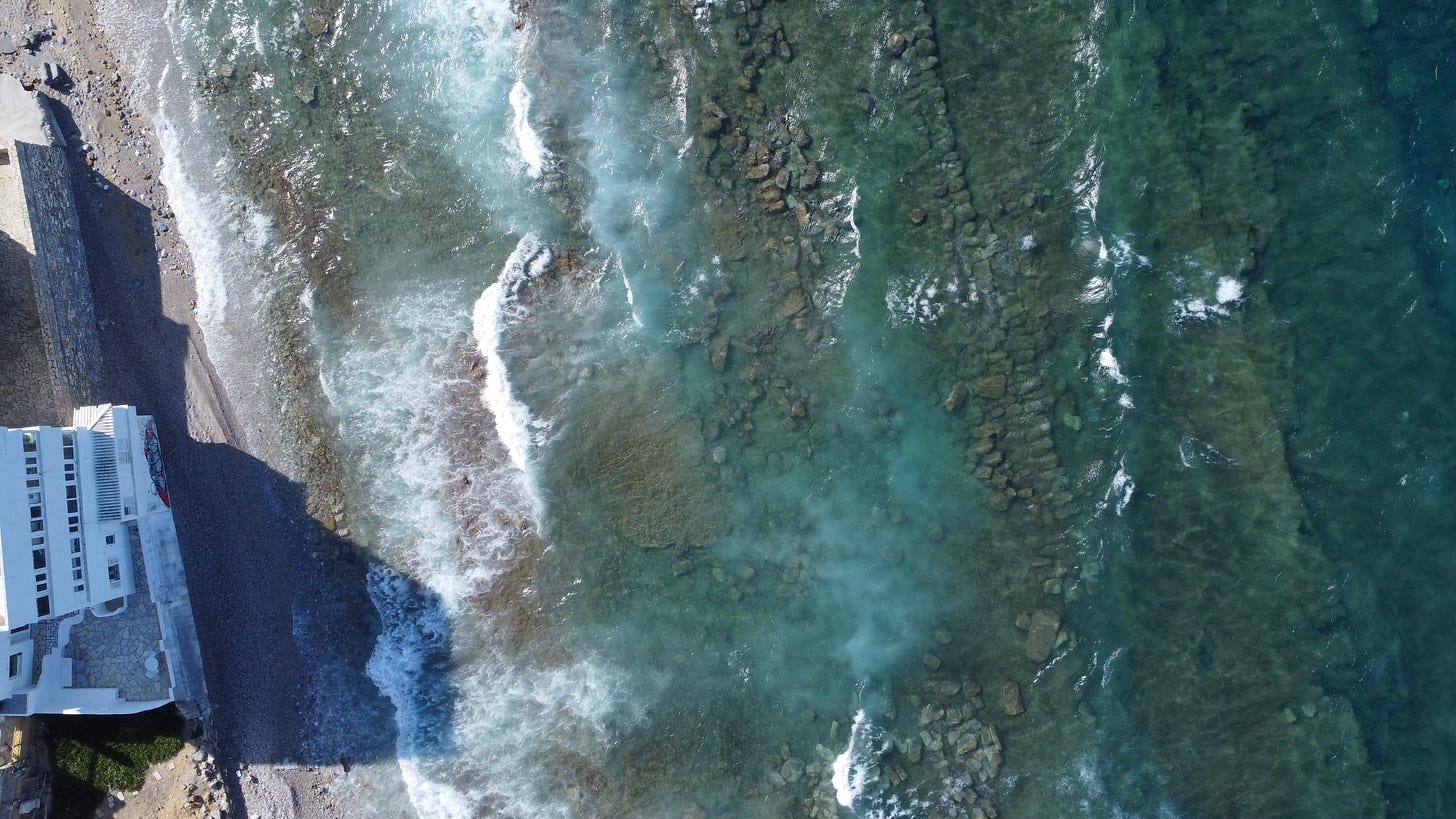

Just as on many a Greek island there are hotels, beer-guzzling Brits and ancient temples, but Grotta beach is different. Just metres out into the surf at this northern point of the administrative centre of Chora, the ruins of a complete submerged ancient settlement are to be seen, other sections having once sprawled under the modern town.

In ancient times, the view here would’ve been very different. The shoreline, and bronze age city with it, jutting out much further into the waves.

On windy days, of which there are aplenty on the Cyclades there’s no chance of sighting the bulwarks of those 3400 year old remains. But when it’s clear, a truly astounding display is to be had. A real life Atlantis that sunk beneath the waves at the end of the late Bronze Age.

I - To The Sea

When Scottish archaeologist Duncan Mackenzie set out from Athens to Phylakopi to embark on the first full-scale excavations in the Aegean at the very end of the Nineteenth Century, on one occasion in particularly bad conditions it took ten days to reach the island of Melos.

Standing out on deck today, the relatively short crossing from Ios to Naxos should only take five or six hours. The crossing from Athens to Syros had taken just a couple, and Syros to Ios not much longer. But that’s when the biting reality of the Cycladic weather began to make itself known.

Stranded on Ios, at the mercy of the mighty wind, I was given my first taste of what must have been a regular occurrence for mariners before the advent of the modern world. An immensely strong squall of wind having formed outside of Athens, temporarily stalling all shipping in the region.

It was the end of the season on Ios and few holiday-makers remained, the usually bustling party island now being reduced to its few hundred permanent residents and a healthy scattering of wild-eyed life-long travellers. I had the particular pleasure of conversation with a reincarnated Atlantean. An Australian who’d travelled to Ios to open a Stargate, she reliably informed me.

Finally setting out at 5pm, we headed out the long way. First to Santorini - where the very real Atlantis-esque metropolis of Akrotiri was inundated by volcanic ash during the middle Bronze Age - before rounding Paros and heading back up to our final destination. A thick black maelstrom of surf churning in the abyss below.

I’d been exploring the ruined citadels of the mainland when I first heard of that submerged city off the Naxian shore. Perhaps it was the dusty October air, maybe the burned off dry grass framing the immense blocks of cyclopean masonry, but the sea appealed immensely at that moment. Just as we know it did to those late Bronze Age mariners who took to the waves from bases like Mycenae, Tiryns, Orchomenos & Thebes over three thousand five hundred years ago to expand their glittering realms into the Aegean.

Yet unlike on the mainland, where for the most part the surviving sites from that far-flung era consist of fortified hill-top centres and overgrown cemeteries. as impressive as they often are, on Naxos, according to my guide book, the remains of part of an entire late bronze age city can be seen, amidst the waves and the tourists off Grotta beach in the main settlement of the island. And not only that but ancient Cycladic ruins too, built by the ancestors of the Mycenaeans from well over a thousand years earlier. Still standing underneath the modern town, Unearthed every now and then by construction work.

So then, after a week amidst the great citadels and capitals of the Mycenaean world, I found myself in Volos, where in myth the famed hero Jason and his argonauts set out on their expedition to distant Colchis across the Black Sea, and where a very real Mycenaean palace has been excavated in recent years. From there we set out for the sea.

That ferry from Ios was itself over fifty years old, a slow moving elegant relic from an older time. Veteran of a thousand storms. The wine-dark sea was calm by then, accommodating even. A few beers and some pastries later and we arrived. Ushered out the doors by expert crewman, and onwards, into one of the most important settlements in the ancient history of the Aegean.

II - On The Island

Heading south from Chora, mountains loom in the blue sky above. Low shoreline stretching off to the west.

To trace that coast further, past windswept holiday homes and plots of farmland, you’ll reach an exposed promontory jutting out to the sea, flanked by a cove on either side. And on top of that crag, stone buildings, of a date well close to four thousand years in the past.

It’s not signposted, and few know of its existence today, but this is Mikri Vigla, once of the most important Middle Bronze Age settlements on the island, with links to Melos, Thera, mainland Greece and arguably most importantly, Minoan Crete. For in the last century a fine collection of anthropomorphic figurines was found here, leading to the proposed identification of this site as a Minoan style hill-top sanctuary, one of the only ones ever found outside of Crete, testifying to the importance of the island during that distant epoch of Minoan hegemony over the waves.

Today most visitors come for the beaches. If they are aware of the history it’s the classical age that takes precedence. And yet, astonishingly, as hundreds of years of archaeological investigation has clearly demonstrated, in terms of its antiquity, Mikri Vigla is far out-shadowed by the other offerings of the island.

From the Fifteenth Century AD, first explorers and then antiquaries travelled to Naxos to speculate and investigate its deep past. By the time the sensational tombs of the long lost Cycladic Civilisation began to be investigated on nearby Syros, it wasn’t long before similar finds were made on Naxos too. A major centre for that remarkable Aegean spanning culture that thrived over a thousand years before even the heyday of both Minoan and Mycenaean Greece in the Second Millennium BCE.

Peeling off the coast toward the vast mountains of the interior, a wilder land opens up. Low hills giving way to rising valleys lined by oak trees and olive groves. Before long in this starkly beautiful land you can no longer see the sea. Dwarfed by Mount Zas, the tallest on the island, one of many sites where Zeus, king of the gods is said to have spent his childhood, genuine Neolithic and Bronze Age remains have been excavated.

At this place where myth and archaeology entwine, gnarled ancient woodland still holds sway, just as it once did on every Cycladic island, from the bleak north of Syros to the rugged peaks of Amorgos. Other isolated remnants of that long ago time before our ancestors began to alter their environments in the Neolithic can still be seen at the museum at the centre of the island, in a classic Cycladic settlement. In design not having changed much since the days of Kastri and Skarkos we’d seen in the days before, separated by more than four thousand years.

Greeted by the wide smile of the curator, in the museum we learn of the very first traces of habitation on the island on Stelida hill. Mesolithic hunters having braved the open sea to reach new edens like this. Great risks bringing even greater rewards.

Finally as the mountains begin falling away, the road leads down to lowlands of the east. Here very few people live today, particularly toward the south, where there are no towns and few holiday resorts. Aside from a few shepards huts and mountain hamlets it is a depopulated land. But this was not always the case. When metallurgy first arrived in the Aegean at the beginning of the Third Millennium BC, here on the south east coast is where people thrived, their settlements thus having largely been saved from destruction for us to visit today.

Given the sheer age of Early Cycladic (3000-2000 BCE) settlements the bulk of evidence tends to come from cemetery sites. Many of which suffered looting long before archaeologists got a chance to undertake studies. Nevertheless a picture of a densely populated Naxos has been developed, in some areas significantly more so than it is today. Coastal settlements existing all around the island wherever flat plains lie adjacent to safe harbours. Of which there are many.

—

Isolated by the Zas range, the southern-most Cycladic settlements at Spedhos, Kalandos and Panormos must have had more in common with the neighbouring islands to the south than their Naxian neighbours to the north and west. Safe from the violent north wind, this was a safe stopping-off point for travellers from distant lands. In clear view of a particularly significant religious sanctuary rising way out in the calm blue. So close and yet so far.

For in those days, at the foot of nearby Keros, stood the island settlement of Dhaskalio, a pyramidal visage constructed of white Naxian marble. Its size, impressive architecture and offerings from almost every island in the Cyclades, testify to its sacred importance to the inhabitants of all the islands. Where we know people came from afar to celebrate and worship.

On a hill-top at the southern end of Naxos, in clear view of Keros, the settlement of Panormos must have been an important place in its day. But ultimately, everything ends. Toward the end of its existence at the end of the Third Millennium BC Panormos was heavily fortified, and like most Cycladic sites, met a fiery end.

The exact circumstance that led to the end of Cycladic Civilisation remain one of the great mysteries of prehistoric archaeology. Climatic disturbances, and natural disasters and outside invasion all being proposed. But by around 2000 BC it was over, and Naxos, just like all the islands of the Aegean, underwent great change. Whilst the Neolithic and Early Bronze Ages are well represented on Naxos, for the Middle Bronze Age we have next to nothing.

Heading back over the mountains, while the south and east go silent, the Cycladic settlements that also existed on the west coast would become the nexus of a new society. At Chora, Kastraki, Agiasos, Apollonas and Mikri Vigla.

It is at Mikri Vigla that we get some of the best evidence for this next phase on the island, for at least some archaeologically verifiable newcomers had by then arrived. A gradual ‘Minoanisation’ being seen from as early as 1900 BC. In the form of settlers or incoming fashions. An outpouring of the palatial civilisation of Crete that can be seen all over the Aegean at this time, and even beyond. A gradual adoption of Minoan styles being seen on Rhodes and all the way north along the Anatolian coast to the Dardanelles, Lemnos and Samothrace, including sites in Anatolia itself like Miletus with its excellent natural harbour.

Other sites with large safe havens for ships to call at like Kea, Melos and Thera became melting pots for people as well as cultures. Nodes in a burgeoning international trade network oozing from Crete to Italy in the west, the Levant in the east. This burgeoning international Cretan system can most obviously be seen at the massive city of Akrotiri on Thera where ornate murals adorn luxury private homes. Though no so-called palatial complexes have yet been found like those on Crete, on Naxos too links to the Cretan palatial elites have been found, in the form of inscriptions in Linear A, a unique Cretan writing system.

Unfortunately, besides Mikri Vigla and a handful of other noted sites in the north west and central parts of the island there is little other evidence for the middle Bronze Age on Naxos, but by the Late Bronze Age all that was to change. For yet another culture had arrived.

Heading back over the Zas range toward the main Chora of the island where all roads lead today, a classical sanctuary sprawls on a low hillside. In the shade of gnarled oak trees evidence of open air worship and communal meals has been found as well as occupation during the earlier Mycenaean age.

In classical times the place was a centre of worship for the demi-god Dionysus, son of Zeus. That trickster god said to have frolicked in Naxian groves during the age of heroes, ultimately becoming entangled with the daughter of King Minos of Crete, Midea after she was abandoned by Theseus heading back to Athens after defeating the minotaur.

While archaeological evidence of the slaying of the Minotaur is lacking, genuine Bronze Age offerings have been found at the sanctuary of Yria. This was was a place where people danced, revelled and spoke to the gods. Cultural traditions that originated on the mainland and may well have flowed directly into the later classical age. For by the Fourteenth Century BCE, though a ‘de-Naxianisation’ never took place, a process of ‘Mycenaenisation’ had certainly arrived.

It remains unclear whether the Mycenaean advance into the Cyclades was based on political expansion, conquest, or cultural and economic, but soon enough in the form of pottery, stone vases, figurines, wall paintings and tholos tombs it can be seen all over the island. It was at this time that habitation seems to have permanently shifted to the west of the island, where shelter from winds, better harbours and efficient control of the straits to Paros could be utilised, as well as being closer to the mainland.

Though people would sometimes move inland to re-occupy older sites, like in the medieval age, from then on, the modern Chora, known as Grotta in ancient times, has the distinction of being the only true urban centre on the island. Unlike many other Cycladic islands which had several competing city states, on Naxos, in classical times just as before in the Mycenaean age, there was only one.

III - By Grotta Beach

In the Fourth Century BC the lauded philosopher Aristotle had much to say on his world. Polymath and teacher to Alexander the Great, that great cornerstone of Western thought wrote as many as two hundred treatises in his lifetime. Among them was one specifically concerning the citizens of the island of Naxos. Though like so much from the ancient world the work is lost today, brief fragments do survive in the works of later writers. All of them speak of famously wealthy Naxian citizens all living together in one place. In one city.

Archaeology and history both suggest that some time in the very earliest days of the Archaic Era, almost all other settlements on the island fell out of use in favour of this single polis. Both it and the wider island becoming synonymous with the name Naxos. By far the largest Cycladic island to have a single political centre. A situation so unique as to warrant a philosophical investigation by the likes of Aristotle.

—

The earliest known reference to a fortified city on the island comes from the works of Herodotus, when he described the unsuccessful besiegement of the place by the Persians in the summer of 499 BC. Later still Atheneus makes mention of the city existing earlier in the Sixth Century BC. A situation that remained the same by the time of the Roman writer Pliny. And though just how long that had been the case was a mystery to those ancient writers today we have archaeology to add to the tale.

Though Naxian prehistory is still an unfinished puzzle, the main chora of the island today is clearly a place of astonishing antiquity. One of the only sites in the Cyclades to have evidence of habitation all the way from the Early Helladic in the Third Millennium BCE to the present, and a good deal of archaeology having been carried out too, though always constricted by the difficulties of modern habitation. Consequently, unlike the Cycladic and Mycenaean levels, the precise locations of the late archaic and classical cities remain unknown.

Some of the very first Western European explorers to arrive on Naxos in the dying days of the Ottoman Empire noted the existence of the ancient city under the modern one. The likes of E. G. Pitton, Joseph Tournefort, E.D Clarke and W.M Leake all writing accounts in the late Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. Soon being followed by the earliest full scale archaeological enquires on the cusp of the Twentieth Century. Excavations have continued ever since.

Perhaps the most iconic sight in the Chora today - just as it was in ancient times - is the remains of the colossal temple of the Archaic (C. 800-480 BCE). Jutting out to the sea on a rocky promontory known as Palatia today, the temple, dedicated to Delian Apollo, whose sanctuary on Delos lies just over the sea to the north, was never actually finished. Though if it had been it would have been one of the largest in the Greek world at the time.

Bounded now by high rises and modern streets, Palatia stills wears its ancient heritage proudly. The small bays on either side likely providing good shelter in the Bronze Age from north and south winds, a double harbour for incoming ships.

In the mid Twentieth Century Greek archaeologist Nicholaos Kondoleon hypothesised Palatia to be the original Cycladic acropolis of the settlement. Though no concrete evidence has been found here thus far, the archaic temple having destroyed any foundations that may have once survived, Kondoleon based his assertion on decades of uncovering ruins amidst the urban sprawl. For on the flat plain opposite Palatia, bounded by a river bed to the east and the hills of Aplomata and Kamini to the north, the city of Grotta once sprawled. Abundant drinking water from the river and salt from nearby marshes providing a solid basis for settled life. It comes as no surprise then, given the excellent position for a settlement that the oldest traces of settlement go all the way back to the Neolithic. With two other hills, also coated in thick habitation layers today, providing easy locations for fortified sites. One now encased in the bastions of a Venetian castle, the other the oldest high school in the city.

When German archaeologist Gabriel Welter arrived in the 1930s to embark on the first modern excavations in Naxos he found a place of immense antiquity. Describing a number of early Helladic buildings, more of which have been dug out during construction work over the last century and can still be seen.

Welter also found what he described as two cyclopean walls of a fortified settlement of the Late Helladic III era. Over which the remnants of a badly preserved second settlement stood. Unfortunately no plans of the digs were ever published, nor any pottery illustrated. Welter refilling his trenches and covering them with sand after he was finished. With the subsequent hostilities between Germany and Greece even leading to the locations of the digs being temporarily lost.

The next excavators to arrive were Greeks, Nicholaos Kondoleon and Vassilis Lambrinoudakis, who would dig on and off at Chora all the way from 1949 to 1985. Like Welter before them, both men found evidence of a significant settlement dating from the Early Bronze Age all the way through to the late Mycenaean era. As well as investigating rich elite cemeteries on the adjacent Aplomata and Kamini hills. The wealth and power of which, they concluded, should imply the existence of a Mycenaean acropolis like those of the mainland.

There is a reason why this isn’t a popular tourist destination like the vast remains of Akrotiri or Phylakopi however. Not only is the proposed location of Kondoleon’s citadel completely coated by medieval Venetian structures, but today much of the lower city itself remains under beach front real estate. Another significant portion, lying underwater.

Though only scant sections of the city have been excavated to date, whenever construction allows it, real insights have been gleaned into just how important the place was in the Mycenaean era and before. Colossal walls, building structures and even a well-built road surviving to the present, the latter constructed in a style most recently associated with similar discoveries made on Crete at Palaeokastro, Mallia and Kommos. Suggesting the existence of itinerant Minoan craftspeople lending their expertise across the Aegean. Connections between Naxos and Minoan Crete that are also seen in fine pottery that closely imitates Minoan shapes and decoration. Naxian styles having leapt from plainware to elaborately sophisticated designs during the late Middle Bronze Age, just maybe with the arrival of immigrant Cretans to the settlement. Perhaps followed by native Naxians developing their own expertise to imitate the Cretan styles to near perfect level. Perhaps with the intention of selling them on for themselves. Naxians making their own fortunes from the craze for Cretan culture. Because when Minoan culture spread across the Aegean, just as the Mycenaean way of life did after, the situation on the ground may have largely been a cultural expansion rather than primarily a population movement. And by 1400 BC the new craze was for the Mycenaean world. On Naxos, like much of Mycenaean archaeology, most obviously seen in the cemetery evidence.

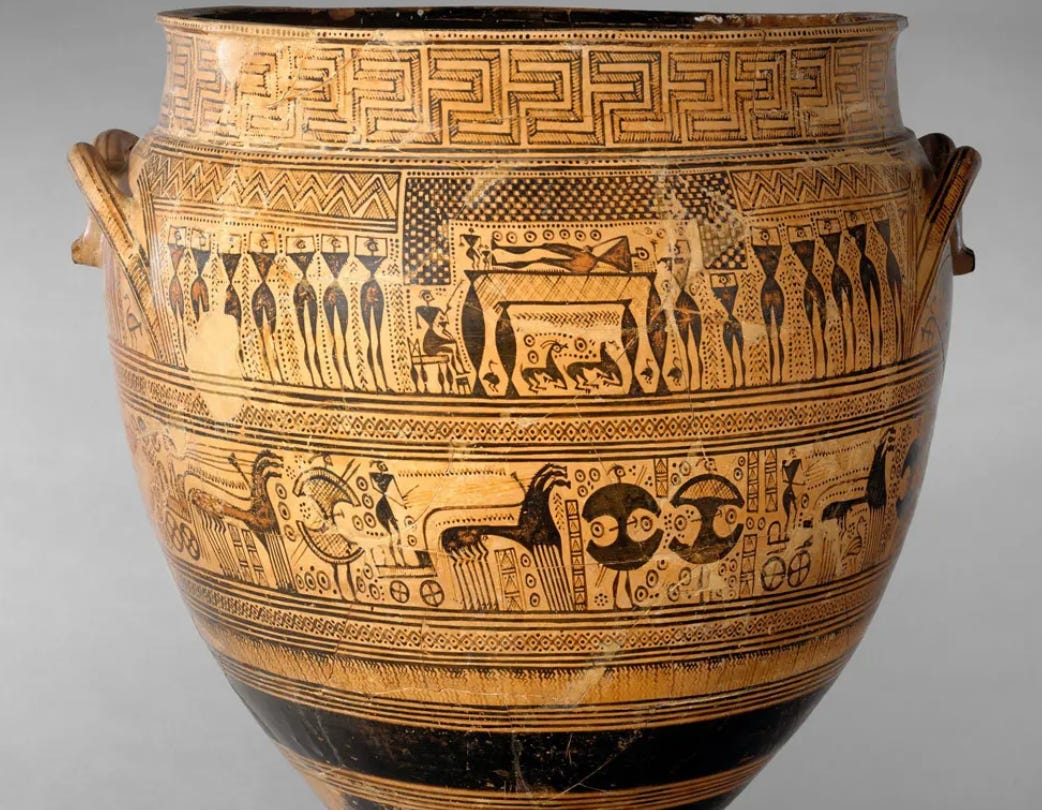

Through a scattering of fragmented Mycenaean burials have been found across Naxos, by far the best finds were made just next to the main city, where two clusters of collapsed chamber tombs at Aplomata and Kamini yielded significant amounts of metalwork from the middle and late Bronze Age, as well as jewellery, gold, seals, and ornate pictorial pottery.

Given the clear demarcation between the two groups, researchers have suggested the possibility of two competing clans or kin groups having held sway over Mycenaean Naxos. An abundance of bronze weaponry and other war gear for horses implies the existence of a sword-wielding horse-breeding class of warriors. Like so many elites around the globe and in the Mycenaean world in particular, there being a clear emphasis on warfare and hunting in the grave goods. Other items including symbols of prestige and insignias of office. Heavily suggesting those interred to have been active in the management of the island and governance of its economy. With clear evidence of imports not just from Crete, but Cyprus, the Dodecanese, Attica, the Peloponnese and even the Argolid itself, these must have been very lucrative positions to hold. Naxos seeming to straddle the line between both east and west, and fascinatingly, uniquely, even after the collapse of the palace states of the mainland by the Twelfth Century BCE, it continued to thrive, making up a core part of a so called ‘post-palatial Aegean geography’.

Things were changing though, and even out here in the midst of the islands, Naxos couldn’t escape. Notably within the chamber tombs at the very end of their existence in the Eleventh Century BCE were found two Naue II swords, a new type spreading across Europe at the end of the Bronze Age. For many researchers symbolising the end of the old chariot style of warfare and coming world of the Iron Age.

—

By the time the Persian war machine under Darius the Great arrived at Naxos in 490 BCE to punish the Greek world, ravaging the then flourishing city, enslaving those who didn’t flee to the mountains, the island had been inhabited continually without a visible break for thousands of years. Enjoying of late a period of true greatness which can be seen in the impressive monuments of the nearby Pan-Hellenic sanctuary on Delos, of which Naxos was a major patron, and in the vast marble quarries and temples of the hinterlands.

By the later Eleventh Century BCE, after the Mycenaean Age, those Naxian survivors of the Bronze Age collapse are thought to have retreated inland from the lower city to the raised citadel. Though today any ruins from those middle years lie hidden beneath medieval structures, a vast Venetian castle complex taking up most of it.

Of note for the curious visitor to the citadel today is the archaeological museum, filled with all manner of fascinating pieces from the long history of the island. Many of the artefacts originating from the cemeteries at Aplomata and Kamini. Still venerated today just as they were in the centuries after the Bronze Age. Though here there wasn’t a collapse as such, ways nonetheless changed over the years, populations dwinded. And as the age of Homeric poetry flourished by the Ninth or Eighth Centuries BCE they harked back to their mighty ancestors. In the long winter nights, battered by howling wind and rain, telling stories of the giant figures who once waged their Machiavellian struggles, voyagers who crossed the known world, and hopes for the future to do so themselves once again.

IV - Sunken City

In its prime the Mycenaean city of Grotta spanned an area of some 35,000 square metres. Today it remains the most extensively excavated of any Cycladic settlement of the late bronze age. Whereas the similarly impressive city of Phylakopi on Melos, with its megaron at the heart of the site, is often argued to have been subject to one of the Argolid centres, on Naxos the seat of a powerful aristocratic elite can be seen. Holding sway over the abundant natural resources of the island as well as the production and export of goods to lands far away. Perhaps alone among the Mycenaean settlements of the Cycladic Islands that we know of, Grotta may well have operated independently.

Though much remains invisible, the Mycenaean settlement underneath Chora was clearly a significant urban centre. With well designed harbour installations and various other public works like cemeteries, workshops and perhaps most impressive of all, no doubt protecting its citizens from their violent brethren on the mainland, colossal city walls.

To walk the tight-nit winding streets of a Cycladic settlement today is to experience a very ancient method of settlement construction. The burrow-like streets with occasional covered walk-ways providing excellent protection from the heat of full summer just as they do the extreme winds of winter. For as long as people have built significant settlements on Naxos they have built them like this. Some designs just work. Even with the heavy Mycenaean influence coming over from the mainland during the Fourteenth Century BCE, it seems that older Cycladic values were merged with a fresh infusion of political might. Creating something new but still Naxian all the same.

For the most part, besides the epic fortress of Aghios Andreas on Sifnos, those most obvious of Mycenaean traits, the citadels, are absent from the Cyclades, Asia Minor too. Palaces with painted walls too have generally not been encountered yet. But at Grotta, typical Mycenaean fortifications can be seen, in a type of cyclopean wall unique in all the Cyclades.

Heading through winding streets from the citadel down to the beach, in the late summer of 2022 I walked over the remains of so long ago. And finally when we reached Mitropolis Square I found what I’d been searching for. For here where wide scale excavations could get deep under the city, almost every level of habitation was revealed, including of course the glory days of the Thirteenth Century BC.

Excavations here and at other parts of the city revealed not just a flourishing settlement but one that was beset by the ever perennial threat in this region. Because some time around 1200 BC an earthquake seems to have struck, which may have been made much worse by the inevitable flooding caused by the low lying nature of the settlement. The old city then seems to have been levelled and a new centrally planned one built on top, with a particular north-south orientation and enclosed by mighty walls, consisting of colossal stone base and mud-brick superstructure. This latest city would survive for centuries to come. A much longer time than almost any other Mycenaean power centre at the time.

Even after the breakup of the palatial system of the mainland, mercantile activity continued, as well as the high level of ship building of the previous century. Though of course, this was a dangerous time, for when central powers crumble, piracy flourishes. Archaeologist Andreas Vlachopoulos calls the Aegean Sea routes at this time ‘anti-monopolist’, and large crater pots from Kos portray scenes of intense sea born warfare, as do others from many other centres. Overall though, unlike many other areas in the Aegean, at the end of the Second Millennium BC Naxos wasn’t just surviving, but thriving. With a community now more Naxian than anything else.

As the so called Proto-Geometric Phase (C. 1050-900 BCE) is gradually approached, narrative scenes portrayed on pottery are often triumphant. Of heroic labours being undertaken by seafarers. Not surprising, for in that coming age the exploits of heroes would be regarded above all else.

At some point a man made channel had been built to connect the Palatia headland to the city, giving it two harbours to utilise. But these efforts had been too much too late. Perhaps as a result of earthquakes, or simply because of rising waters evidenced by sand deposits, by the Eleventh Century BC, the northernmost part of the city had been completely submerged, a quay and other houses only just surviving above the waves.

We don’t know how or when exactly, but at some point the decision was made to abandon the place entirely, the remaining population moving their homes up to the Kastro Hill where the archaic and classical cities would develop. There, life continued as it had. The old city turning into a place for the dead. Random burials eventually being organised into a geometric era cemetery, with enclosures for tombs. There, where the still visible walls of the city stood above ground, individuals were carefully buried alongside their vaunted ancestors. Finally, a large earthen tumulus was built over the geometric cemetery at Mitropolis Square. Likely becoming a focal point of worship and commemoration of those who came before. The impact they had on their descendants being so profound that they could not, or would not abandon their city.

Heading out of the Mitropolis Museum and down toward the sea, a scattering of Mycenaean edifices can be spied, though almost all have been covered up for protection since their excavations. Near the western end of the beach three Early Cycladic houses can still be seen on either side of a narrow lane. But it is out on the beach itself and the surf beyond where the best remains of all are to be found. Near perennial winds make the task difficult, but after two days of trying, the city underneath the waves can clearly be spied.

Only future investigations will reveal more of the secrets of this Bronze Age powerhouse, but until then aerial photography will have to suffice.

Though new populations would continue to arrive during the course of the Iron Age as the great reshuffling of the Greek colonisation period began, like most places, it is entirely likely that many inhabitants of the Chora today are descended from those heroes of long ago. Only future excavations will reveal what other wonders lie hidden under the urban sprawl.

If you’d like to learn more about the Mycenaean world, then here is a video I made earlier on another fascinating archaeological site from that axial age. Thanks and see you next time.

I'm in Central Asia. Let me know if you want video of something! I wanted to go to Taraz (still am) to go see the battle where the Arabs beat the Chinese but just found out historians don't know the real location of this site. Anyhow, if you want to send me somewhere in Kazakhstan to see footage for your future videos, I'll be here for the next few weeks!