In the hill country north of Kandahar a very traditional way of life is the norm. Camel herders and horsemen still drive their herds across the high valleys; braving sandstorms, snakes and hyenas in that rugged land thousands of feet above sea level. Heading toward the roof of the world.

By the mid Twentieth Century life hadn’t changed a great deal here since the days of Alexander the Great, known in these parts as Iskander. That great conquering warlord who first gave his name to the city well over over two thousand years ago.

By the time Sylvia Matheson arrived in the mid 1950s, westerners were still very new to Afghanistan.

A journalist and amateur archaeologist from Britain, she’d been yearning to set foot inside the secretive highland nation for years. Once having stood at the borders of Iran’s eastern desert gazing with wonder over the snow peaked mountains to the east.

Now, invited by French archaeologists Jean Marie and Ginette Casal to work on their well established archaeological dig as a team leader, she not only had her chance to work in that most elusive of Central Asian countries, but would write a lively account of her adventures. Though sectarian strife and iconoclastic fury still simmered underneath the surface, the 1950s seemed an innocent time filled with hope for the future, and besides rip-roaring descriptions of the archaeology itself, her ensuing book ‘Time Off To Dig’ is filled with touching and genuine interactions with her Afghan workmen and their families. A life which would soon some crashing to an end.

The Casals had already been in Afghanistan for years by that point, and they would remain for longer. Their site was one one the most important and baffling ever discovered in the vast landlocked mountain nation. For a time one which captivated the world.

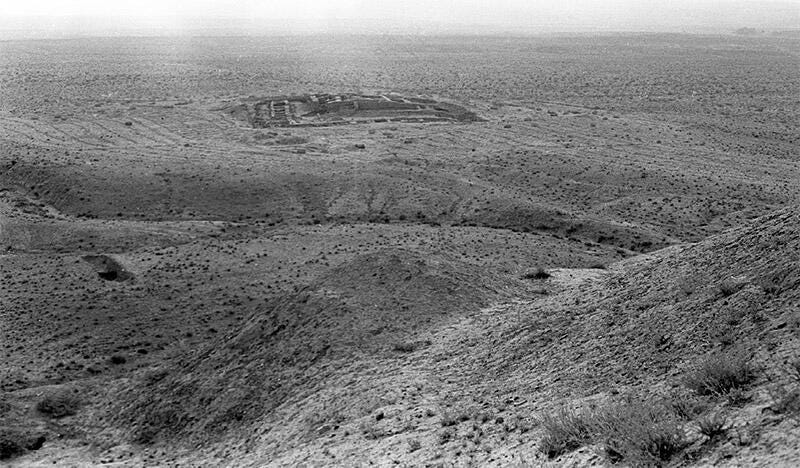

Today Mundigak oozes along a dried up river valley. Dusty ground and rising mounds home to tarantulas, giant ants and not many signs of the settled city life which once thrived here more than four thousand years ago. The changing course of the waterway in antiquity sounding the final death knell of the place. So long ago as to be near unfathomable.

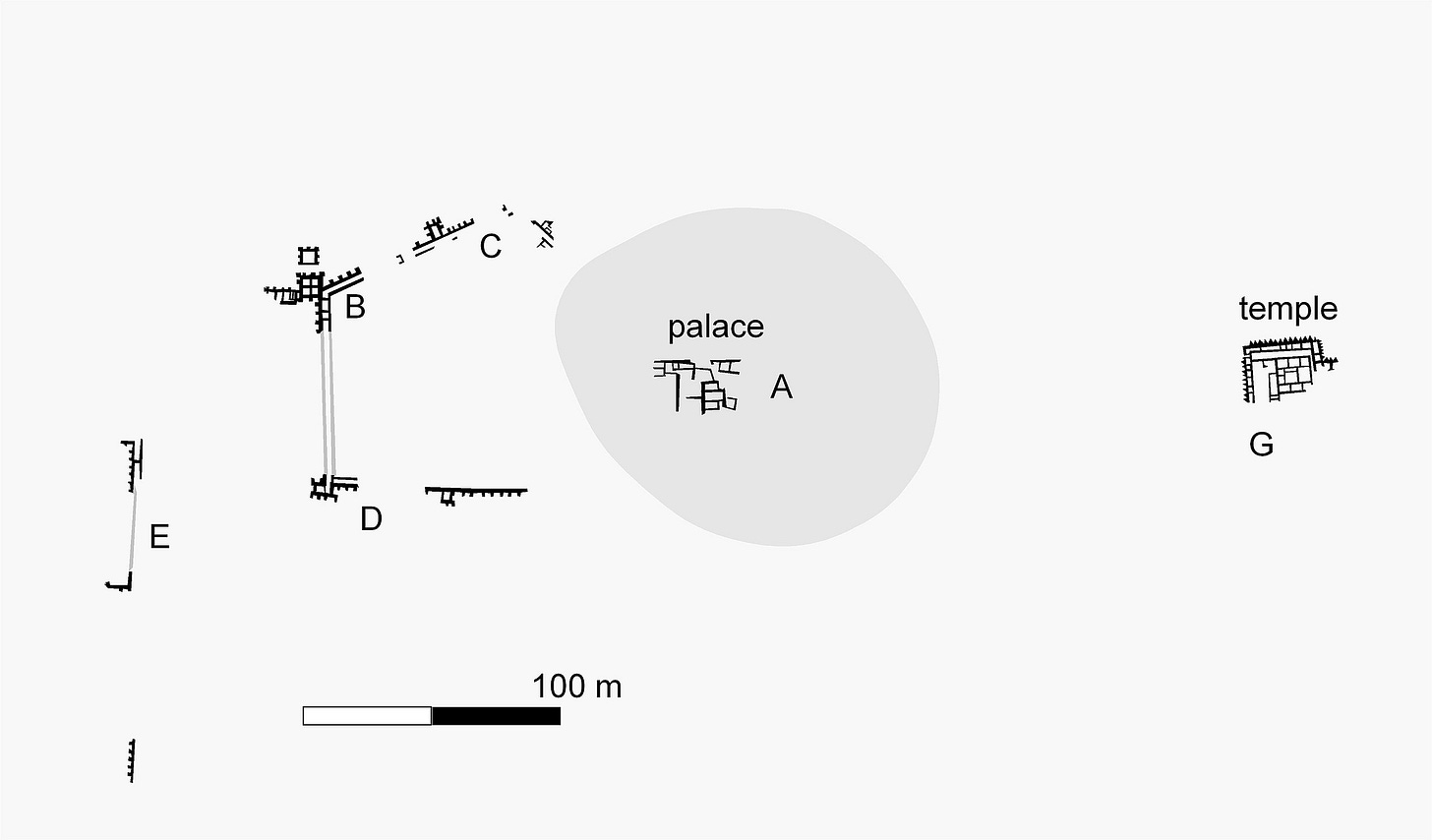

Wasting no time, not long after she arrived the Casals took Matheson to see the most iconic section of the site, recently having made headlines the world over. Already half reduced from its original height of around sixty feet, the man-made tell known as Mound A was nonetheless still wildly impressive to behold. For once this had been a focal point of the city and naturally one of the main focuses of the dig.

Cutting down from the upper most layers with spade and trowel, at first the refuse of Late Bronze Age nomadic wanderers had been carefully catalogued and removed; post-apocalyptic squatters eking out a living in the refuse of the world that came before. The final years of life here before the record goes blank for good.

Underneath, the ruins of a vast monument were soon uncovered, an extremely large building covering almost the entire mound having been thrown up at the very end of settled life here.

And yet the further down you go the story only becomes more complex. For underneath that mighty monument stood the layers the Casals thought to be the very apogee of the site.

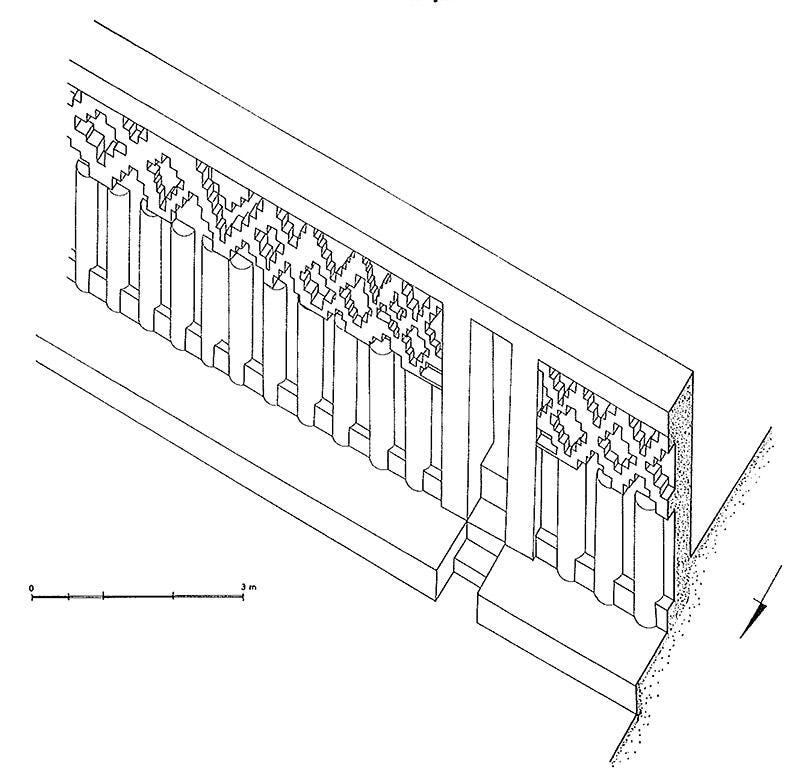

A complex corridor-lined citadel was to be found. Made up of terraces, rooms and columns, surrounded by an elaborate array of walls and battlements. And at its heart, one of those rare buildings of antiquity that leaves a lasting impact on the enquiring mind. A particularly sturdy construction; its outer facade lined by painstakingly maintained colonnades of white-washed mud brick on a carefully built platform, still standing in the 1950s to around four and a half feet high.

It’s thought another layer of colonnades would’ve originally rested on top of the base one, a platform or bench around two feet wide running around the base. The tops, decorated by intricately crafted merlons arranged in a battlement design. Amazingly the bases of this second level of colonnades would’ve been vast. Judging by the diameter they may have been even larger than the surviving ones.

When Matheson arrived at the site thick coats of whitewash still clung on to the outer facade of the building just as they had since they were first carefully layered on by artisans in the Third Millennium BC. Ginette Casal counted twenty nine separate layers on one particularly well preserved side room.

Brilliant red ochre was then still visible above doorways. Leading to suggestions by scholars of the time that the Colonnades at Mundigak could only be the remains of a great palatial temple complex, such as had been recently excavated at sites like Ur in Mesopotamia.

Though the whole structure was made of mud brick architecture, the entire eastern side having already been lost to erosion, it had been immensely sophisticated in its day, match for anywhere in the world. Massive sturdy walls, hearths, basement storage units and staircases to upper floors all surviving to be excavated.

And during the long gone days of its glory this complex would’ve glistened over the valley below, visible for miles around on the approach to the city, smoke rising from pearl white walls. Anyone approaching from afar would’ve been awed and dazzled long before they reached the city gates. Undoubtedly it had been built by a people with a strong artistic sense.

Mundigak had been a sight to behold, and its people knew it. Clearly here had existed one of the great cities of Asia. Rich and powerful; outward looking, and as far as Matheson was concerned, strikingly Mesopotamian.

Due to the great similarity between mud-brick and natural mud, sites like Mundigak are incredibly difficult to dig, and heartbreakingly the intricately built colonnades of that astounding palatial complex had already begun to erode away by the time Matheson arrived. Just twelve months after their first uncovering from thirty feet of sand. During which time its labyrinthine rooms and passageways had been painstakingly hollowed out of their tomb of four thousand years by well drilled Afghan workmen. Every particle meticulously removed by hand.

The artefacts so far pulled out of the earth had been impressive too. Beautiful goblets with large birds on them having being found the season before; reminiscent of peacocks Matheson thought, or turkeys.

Humped bull figurines had been found too. Similar to Harappan carvings from the contemporary Indus River Valley. Carnelian jewellery, blue beads & green steatite seals further cemented the economic and perhaps societal links clearly fostered with the Indus Valley Civilisation to the south and east.

And just like other Third Millennium BC sites in a wide arc across Eurasia, from Oman to Greece to Egypt to Central Asia those elaborately crafted sealstones had not just been decorated with ornate symbols but pierced by holes, likely intended to be hung on a chord around the neck. Worn by priests, traders, kings or all of the above.

Evidenced by the wide ranging goods and artefacts traveling thousands of miles across the known world by sea and land, this was a linked up world.

The stamps seals at Mundigak become gradually more elaborate as time goes on until the last layers of the site when entirely new designs are added. During the 1950s, in the shadow of the Second World War, the theory for this shift rested firmly with the military. Invaders being thought to bring new ideas to the city in the last centuries before its final end. Though today as the pendulum ever swings back and forth internal societal change is favoured.

Looking down from Mound A in that heady summer of 1955 Sylvia Matheson could see a massive and imposing site stretching across the entire valley floor. Only a tiny fraction having been excavated. Many other tells could be seen too stretching to the horizon. All of them man made, wide terraces crumbling over hillsides.

The modern village of Mundigak, the ‘Village of the Small Mound’ was likely built on ruins also. And that’s where Matheson came in, for now she would supervise the uncovering of Mound B.

When the pyramid builders of Egypt threw up their mighty monuments to the heavens in the Third Millennium BC, the city of Mundigak was already old. When the priest scribes of Old Sumeria first made the revolutionary leap to recording knowledge on mud brick tablets in the legendary lands between the two rivers there was already a thriving settlement here. Even as the scattered tribes of Europe went about their hunter-gatherer existence just as they had for millennia, some kind of civic life had already taken hold in this mightiest of cities on the Helmand river.

As Sylvia Mathson beheld the thirty foot high site surrounded by a deep moat now designated as ‘Mound B’ she had no idea what she would find, but as the weeks went by the place gradually revealed its secrets.

At first Mound B seemed to be a sizeable castle. Enormous heavy stones acting as foundations for a thick complex of mighty mud brick structures. Large square buttresses and thick outer walls surrounded residential areas and domestic structures. This had clearly been an important and well designed part of the city.

The Finds were fascinating and unique too. Notably a small marble table with six inch legs being uncovered, surrounded by numerous earthenware goblets and drinking flasks. As far as Matheson was concerned they resembled the sort of table set still seen in her day at the courts of Indian princes.

And yet just like urbanisation itself, Mound B was a place of contrasts. Though the site seemed to have been perfectly aligned with Mound A with the utilisation of masterful town planning. Its buildings undoubtedly designed to look good, with an artistic sophisticated slant; one corner seemed at least for a time to have been a kind of shanty town coated in animal bones and several feet of refuse.

As excavations continued it was hypothesised that Mound B had been a residential area whereas Mound A might have become a spiritual temple palace complex. Matheson was reminded of the recent excavations of Ur in Mesopotamia and Leonard Woolley’s wide ranging hypothesise on worshipping on high places.

And then a portion of a city wall was found criss-crossing the mound, apparently with little regard for the previous grid planning. Ultimately more walls were found. Not just Mound B but the entire city being encircled by a much larger than expected series of mighty bastions.

And yet still so many mysteries remained. There were more mounds yet to dig. And beyond that way off into the rest of Afghanistan surely there were other cities too. Only a small part of the overall picture being found here by chance. Mundigak did not exist in a vacuum.

The most recent Radiocarbon dates placed the earliest occupation at Mundigak in the Fourth Millennium BC, but other estimates put it further.

By the Third Millennium, copper and tin appeared, linking the place with the outer world. Sources of tin are not far away perhaps hinting at part of reason for places success, but copper had to be brought in from afar. One carbon date gate a time of 2650 BC for the mature city, give or minus 300 years for the very new technology at the time.

And yet, it remains a curious fact that in hundreds of miles of open land just a handful of scattered sites from the Early Bronze Age have been found in Afghanistan. But what sites they are. In recent years some similarities have been found between Mundigak and the settlements at Kot Diji, and Deh Morasi Ghundai, but due to the fragmented nature of research the rest remain buried or lost.

There are of course similarities with the Indus Valley Civilization, almost certainly major trade partners of some kind, material goods being found relatively in abundance. But the Indus is still quite far away. To the east, just over the border in Iran there are similarities with the ‘Burned City’ of Shah I Sokhta, one of the greatest early Bronze Age sites every uncovered. Due to the similarities between the two metropolis some scholars have even argued for an ‘Early Bronze Age Helmand Civilization’. The distances between the sites however was still massive, surely quashing any idea of a singular unified kingdom. Independent polities sharing a similar culture, like Sumeria, being much more likely.

Even by 1957 when Matheson returned to Afghanistan for the last season at Mundigak the white-washed colonnades had already all but disappeared. There being no hope of permanently preserving it, besides dig notes and black and white photographs it is lost.

And yet by that time after seven consecutive summers of digging, an astonishing picture of an early Bronze Age polity had been revealed.

As the dig progressed more mounds had been dug. Mound G revealing a particularly unusual assembly of structures. A huge rectangular enclosure within thick walls of mud brick with a series of courtyards and small rooms opening out from each other decorated with red paint, burnt stones and mud brick dais. The excavators surmised it to be a kind of temple.

By that time cemeteries had been uncovered also, containing individual graves along with pottery associated with Mound B. A little of the story of Mundigak could finally be told.

In the later Third Millennium BC, during the Ninth level of occupation, Mundigak had been a truly astonishing place. Originally having lived on Mound A the citizens seem to have made a conscious decision to move domestic life to Mound B, keeping their original home as a sacred centre with almost no domestic items being found. Mound A was levelled and a vast colonnaded monument built.

Around three sides of the temple were a number of much smaller rooms, or cells. Containing a vast wealth of hoarded items in underfloor storerooms only reached from above. Some contained bone needles and pins. Others goblets with beautiful patterns arranged in series according to size and pattern. Whether this was tribute stockpiled by a priestly class or stashed items for import or export has remained in debate ever since.

At the city of Ur Leonard Woolley had found a similarly majestic great temple at the ceremonial heart of the metropolis, with side rooms attached that he associated with ministers of war, justice, agriculture and finance. Linking up large courts and public rooms for administration.

Here at Mundigak behind the colonnade had been a maze of rooms also. Where many unusual and elite looking items were found. Terracotta drains served the buildings. Female figurines looking like mother goddesses, spindle whorls, cups and bowls of alabaster, marble pestle and mortars, and perhaps most interesting of all, seals of a geometrical nature, a proto-writing system perhaps. Made of steatite, and even bronze, scattered with a few other bits and pieces of metal.

Just maybe, not unlike Ancient Sumeria, rent, tithes and offerings had been paid to the gods here. So temples had to have large store rooms around central sanctuary where people paid their dues.

But then, something happened. There was no fanfare, there may have been no inclination of it happening at all, but by 2100 BC Mundigak had passed the peak of its glory.

After flourishing over a span of time longer from the Norman conquest to today the days of that mighty city of the prehistoric Afghan highlands were numbered.

As so often is found in cities of the ancient world, the glorious apogee was followed swiftly by a fall. Very early on the narrow walkways in front of the Colonnaded temple palace of Mundigak had been found to have been blackened by fire, corridors strewn with arrowheads, spears and sling pellets. Prior to the destruction event, hastily built fortifications may already have been thrown up in the form of a defensive wall across the northern face of the Colonnades. To no avail. There was a short, sharp struggle followed by a fire. It may be that most had already fled.

No bones were found in situ from that attack which blackened the walls, though one shallow communal grave was found at the foot of Mound A.

It’s difficult to say what happened on that day, but the archaeology clearly suggests streets and foyers, granaries, palaces and temples alike all being put to the torch. The great centre of the city becoming a funeral pyre visible for miles around. Visible from every corner of the valley.

But people did remain. Though in what state we cannot say. Afterwards the entire mound was turned to a new purpose. A vast monument to inter the remains of the earlier age. Whether the citizens of Mundigak were put to work on this new construction project we simply cannot say.

I am reminded of the burial tumuli placed atop the Early Helladic sites of Lerna and Thebes at around the same time, toward the end of the Third Millennium BC, and like in Early Helladic Greece the simple pottery and material goods of the conquerors stand in stark contrast to the majesty of those who came before. This eleventh level was much less sophisticated. A cultural break suggesting a new era and perhaps a new people. That last huge building they placed atop the mound slowly deteriorating until finally, perhaps aided by earthquakes that occasionally still wrack the region, it fell to ruin. Home now only to Shepards and nomads.

When Mundigak had first been settled trees had coated those fertile river valleys on the edge of the Himalayas. By the end of the city not much remained. Consumed by the insatiable maw of urbanity. Timber has been hard to come by ever since, and yet mud brick architecture was the norm here, a city could survive without wood. Much more devastating was the drying up of the riverine waterway that had first brought life to the valleys.

By 1000 BC when the last inhabitants of Mundigak clung on to some semblance of the sophisticated city life of their ancestors the surrounding valleys were already near incapable of supporting life. Soon enough the people would move on, and the place consigned to oblivion.

By the end of the 1950s when Matheson geared up to leave Afghanistan for good, she saw the first hints of what was to escalate in only a few short decades. The Russians too investing in the country in full force.

Today, sprawled on a desolate plain, Mundigak yearns for further investigation. Its stunted and stalled investigation left as a reminder of the common heritage, humanity and lack thereof that unites us all. Mundigak is for everyone or no one at all.

If you want to learn more about the Third Millennium BC then here is a documentary I made about the contemporary Akkadian culture of modern day Iraq:-