On the north coast of Wales, the great crest of Snowdonia rises like a palisade on the western horizon; perennial bastion of the venerable kingdom of Gwynedd which once ruled in these parts.

Astride windy cliffs by the foothills of that mountain range, a great headland juts out into the Irish sea. It was here in ancient days well over three thousand years ago that copper was mined by the great Bronze Age metal barons; international wares moulded and shipped to all corners of the island and beyond.

The cairns and settlements of that distant time can still be seen amidst the tourist trains and guest houses. The modern town of Llandudno oozing and stretching along the coast.

But the copper mines of the Great Orme aren’t the only relic of the past in this ruin-strewn land. Just an hour’s walk inland along an estuarine river valley, stands Conwy. One of the most complete medieval walled settlements found anywhere in the world. It’s still standing circuit complemented by the immense castle built here by the English in the Thirteenth century.

Today Conwy is the very epitome of a medieval settlement in Britain. Immaculate round towers draped together with precise curtain walls, drawbridges and killing zones. And yet, Conwy Castle is a relatively recent construction, thrown up by foreign occupiers, living in a fenced-off pale. The herculean visage of Conwy Mountain and its Iron Age hill fort ever looming to the west, persistent reminder of the ancient inhabitants who’d once been the undisputed masters of this land.

And there is another reminder too. Another castle, hailing from a more modern age. Just over the water from Conwy.

For hundreds of years before the English ever came near to this region, it was from here that the rulers of the land administered their kingdom.

This is Castle Deganwy.

Though little remains now besides crumbled towers and ruined foundations, it’s famous in myth, history, and archaeology alike. Long before the Thirteenth century wars of Edward Longshanks.

For it is at Deganwy, arguably more so than at any other site in Wales that a powerful Sub-Roman kingship can be brought from back from oblivion. When excavators dug underneath the later medieval foundations here in the 1950s not only was a royal centre for a Sub-Roman warlord rediscovered, but firm evidence of links to a burgeoning continent-spanning trade network immediately following the end of Roman rule in Britain

During that mist-shrouded time of legend when there is usually almost no evidence at all to go on, this place is one of the most important to be found anywhere. In archaeology as well as in myth.

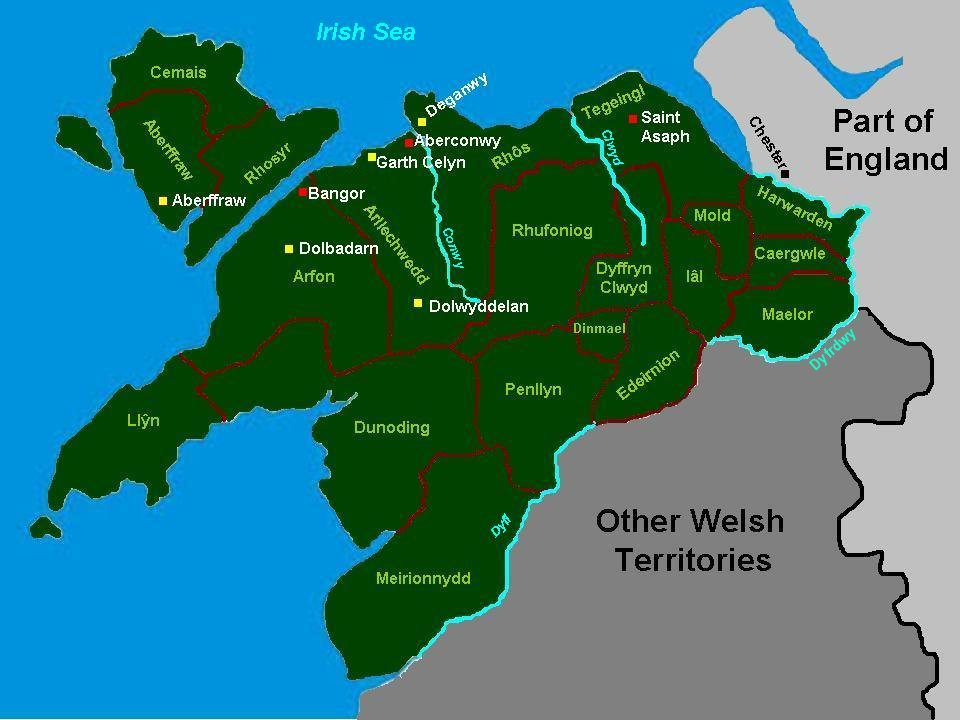

We know that from here a dark age warlord, or king ruled, perhaps moving between similar bastions on distant Anglesey and the Lyn Peninsula too. Just maybe administering and politicking over one of the largest realms in Britain.

II - ‘Dragon of the Island’

Britain’s Fifth and Sixth Centuries are its most underrepresented of all in terms of historical evidence.

Where once elaborately maintained Roman towns and cities sprawled over the lowlands, linked by mighty road networks, way-stations, and fortress bastions; their roundhouse living British subjects eking out a life in the wild borderlands beyond, now almost no evidence is to be found. The literate city life and currency of the Fourth Century having given way very quickly to isolated holdouts and mass decentralisation.

In truth there is very little archaeology to go on when compared even to the Iron, Bronze and Stone Ages that came before.

What does very quickly become clear when studying the still sizeable mass of evidence though is that the long span of history had apparently very quickly been interrupted. In the space of a single generation a kind of post-apocalyptic society taking over in vast swathes of the island.

In written history too, besides much later myths and legends compiled into purported chronicles and histories, a mere handful of contemporary documents are all that remain. Scraps of information rescued from the darkness.

Even the much respected and pored over histories of Nennius & Bede were written much later, in the Seventh and Eighth centuries when intellectual connections with continental Europe had resumed, Britain gradually becoming literate and relevant once more.

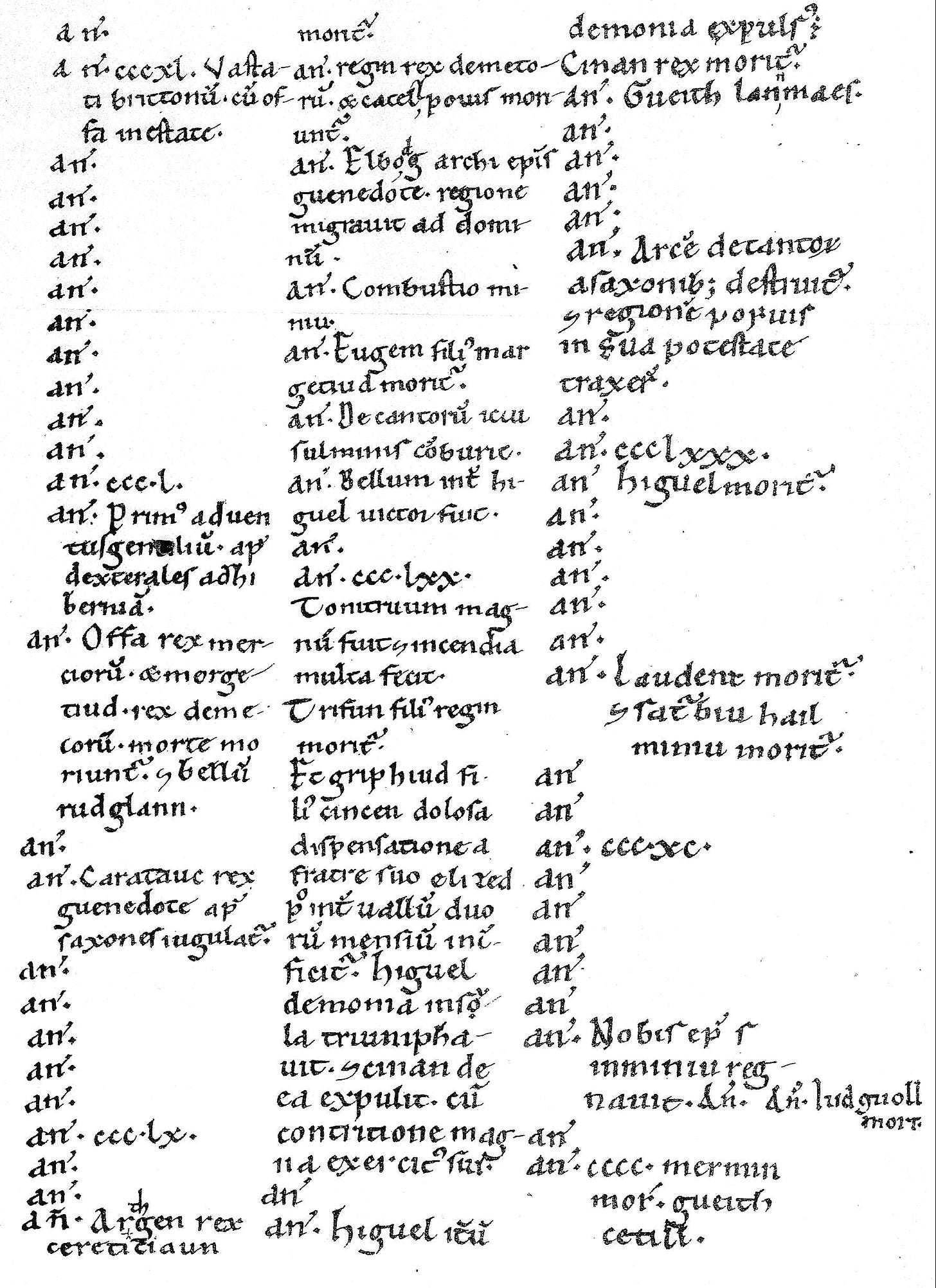

And yet, at Deganwy, records do remain for those wastelands of knowledge in the Fifth and Sixth centuries. Amazingly, a work which references a king who may well have ruled this place. For in Gildas’ famous work ‘On The Ruin of Britain, the most complete of all sources for the Sixth Century, he includes is a historical list of kings along with brief pieces of information, and one of those rulers, Maelgwyn Gwynedd, the so called ‘Dragon of the Island’, looms large in traditional stories centred on the power-base here.

It is incredibly rare to find Sub-Roman settlements anywhere, let alone one with associations with a known ruler. But in later generations, Deganwy, as well as the Conwy Mountain on the other side of the river, and a number of other sites in the immediate vicinity were associated with Maelgwyn. The oldest mention seems to be in the Annales Cambriae, an albeit later, historical account, originating in the Tenth Century, but known to contain much older information within.

Maelwgyn is thought to have dominated Northern Wales, with power-bases in Anglesey, Snowdonia and the marches too, the gateway to his realm. And what a spot this must have been for a dark age king. Perched on a dead volcano, wooden fortifications adapted and moulded around natural buttresses provided by geology. With clear visibility on every side, it’s an excellent location.

And according to Gildas, Maelgwyn was a vicious tyrant, an idolatrous usurper and all round terrible individual. When thinking of later medieval kings who angered the church, like the Holy Roman Emperor Henry I and murderer of Thomas Beckett, King Henry II, Maelgwyn sounds like a king all right.

If the kingdom of Gwynedd had indeed been one of the most powerful realms in Britain, and archaeology supports this too, there is a good reason for his success. In peripheral areas where the Roman way of life never fully take hold, the still militarised citizens had less far to fall. Continuing their way of life more easily than those in the more advanced lowlands who relied on foreign imports and commercial activities for their very way of life. Out here on the western sea ways the fall of Rome doesn’t seem to have been nearly as severe.

III - Foundations

For me, getting the train to Wales has always been a strangely mystical experience.

Amidst the rising hills and the woodland, if you’re lucky when glancing out that window, you might catch a glimpse of Offa’s dyke; colossal Early Medieval earthwork stretching from sea to sea. Closer scrutiny reveals hill forts, mountains, and of course, castles.

On this particular journey, hugging the north coast, I see distant wind farms guarding the hazy horizon, beached battleships, near unfathomable leagues of muddy sand, and very few settlements.

When finally we pull into Conwy station I can already see medieval fortress walls. Here, just as it always has, the castle dominates everything. Standing guard over pubs and great restaurants, holiday makers and hikers, and of course, the city walls.

Down in the bay, by tug boats and fishing vessels, you can see all the way down the estuary to the sea. But on the far side of that water where two mis-shapen mounds rise, a short walk over the bridge, along pebble lined paths, that is Degnnwy.

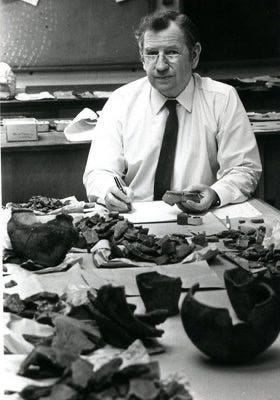

More than half a century ago now, another figure came here. An archaeologist. Also interested in that ancient castle, its crumbling ramparts all but gone today. His name was Leslie Alcock, one of the most famous of all archaeologists in that time.

For these were the halcyon days of the 1960s and Alcock also embarked on excavations at a number of other sub-roman sites, most notably Cadbury Castle in Somerset. Widely publicised as one of the best candidates for Camelot, mythical home of the legendary British king, Arthur.

But outside of the very successful and lucrative media campaigns launched by the Somerset digs, Alcock's interests ranged far and wide all over Britain. Arguably his most brilliant written work concerned itself with the Picts and the Welsh as much as the southern British and Cornish. His digs took him all over the island, from the Somerset Levels to Loch Ness. From South Wales to Southern Scotland. Excavating at many of the most famous sites from Sub-Roman Britain.

In importance however arguably few were surpassed by Deganway, potentially the only one with a good argument for its rule by a historically verifiable king.

When Alcock and his team first came here in 1961 the place looked much the same as it does today. Perhaps a few less houses and more green fields but overall largely forgotten and untouched down the centuries.

And when they started to dig, making trenches beneath Thirteenth Century stone bastions, and continuing to do so for another five years to come, it wasn't long before the evidence of those long lost years before began rising to the surface. For Deganway has much older foundations than those of the high medieval princes of Gwynedd.

It soon became clear that like most hill-forts in Wales Deganwy’s history stretched far back into the mists of time. With evidence being unearthed of life during the Roman period. The recently abandoned ancestral tribal centre on Conwy Mountain was located just to the north, a nearby fortress of the imperial occupiers to the south.

Unfortunately though we can say little with certainty about the Roman era here, we know that after the Romans left it became truly important.

High up on the rocky vantage point here, well over a hundred metres above the sea, the place was undoubtedly a safe haven during those uncertain times. A refuge from seaborne Irish raiders and neighbouring Romano-British warlords alike. The fortress itself, now little more than ditches and mounds, is modest to our eyes. Constructed of wood, likely with room to comfortably host a few hundred individuals at most, trusted warriors to line the fortification walls. Probably only the larger of the volcanic mounds was occupied.

Wooden palisades line the hill-top, a scattering of houses and huts for the kingly retinue within. Smoke billows from hearths and smithies, old tracks line the hill-side from walled gateway down to the shore, where tiny coracles come up to sell their wares. For above all else it was access to the sea that made life here possible, arteries to lands far away.

In an island with few settlements to see at all, this was one of the most impressive, and no doubt a beacon to travellers from afar, who came to barter for goods and knowledge.

And beneath that rocky stronghold, clustering around the timber halls of a strongman and his family, there may well have been a fairly sizeable civilian settlement. The beginnings of state formation perhaps in the Sub-Roman world, driven by the needs of those seeking protection; any sort of stability they could get, from a battle-hardened warlord.

And of course we have the material objects too. Astonishingly the very same style of pottery as is found at Tintagel, Cadbury Castle, Dinas Powys and even much further afield at Dunadd, royal capital of the Dal Riatans, in Ireland and all over Sub-Roman Britain. A dozen of these shards had been imported from the Mediterranean, suggesting far-reaching contacts of those who ruled here.

It’s widely assumed that the ruling dynasty of the fledgling kingdom of Gwynedd had their main powerhouse at Aberffraw on Anglesey, but many other citadels have been excavated from this time too, at Dinas Emrys, Garn Boduan, Dinorben and more. It’s possible that like the later medieval rulers of Wales leadership was peripatetic, with the court constantly moving on a circuit between elite centres.

If Deganwy had indeed been a capital of Gwynedd, even for a short time, or of some other kingdom now lost to the ages, the threads of fate had other ideas for the place, it entering a steady decline over the centuries, particularly as the focus of Gwynedd solidified on Anglesey and the innards of Snowdonia.

According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle the first Degannwy met its final end in 812 when it was struck by lightning, burning to the ground.

The small-folk never forget its once held importance though, unlike many other areas in Britain, entering into myth and legend.

IV - Legacy

By the early 1200s the wooden hall of the Sub-roman power brokers had long since rotted away. The warriors and traders of those distant days having already dissipated into bardic myth and legend. Today it is the towers and foundations of that era that remain. Stone-built masonry crafted by the various powers who came this way in the High Middle Ages.

For in that later age some eight hundred years before the present this area of Wales was a battle ground once more. The frontier-zone in a titanic conflict waged by generation after generation of French speaking English kings for control of the northern Welsh kingdom of Gwynedd. The last to resist English expansion.

In 1210 in the latest of those hard fought battles, Englishmen came to Deganwy.

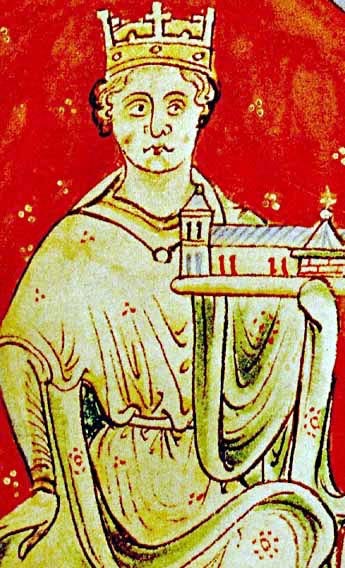

Scarlett-clad knights and rumbling siege engines rolling out from Chester by the orders of the Plantagenet King John. The castle still prospered in those days. A stone built keep having been thrown up here to guard the western passes into Snowdonia, not by the English but by a native Welsh ruler. Perhaps the greatest of all. An immensely impressive king in all but name who dominated Wales for over fifty years. Playing enemies against one another with clever statesmanship and mopping up the rest into his ever growing state amidst Machiavellian power struggles of epic proportions. He was Llewelyn mac Iowerth, better known to history as Llewelyn the Great, and for a brief time at least Deganwy was his castle

As a child Llewelyn had watched his two uncles squabble over the sought after succession to the throne, as well as the battles of the multitude of other rulers waging similar struggles throughout Cymry. Yearning above all for a unified and strong homeland, by the year 1200, through sheer military might, he'd successfully wrested control of Gwynedd. But he wasn’t finished yet.

Not just a great tactician but a brilliant diplomat too, Llewelyn was able to forment an alliance with the embattled english King John, ultimately marrying his daughter Joan in 1205.

By 1208 Llewelyn had seized the entirety of neighbouring Powys, leaping to the opportunity when it’s king fell foul of John. By 1210 however relations deteriorated. Perhaps fearing the ever growing power of the Welsh king, John invaded.

Faced with the overwhelmingly powerful siegecraft of the Earl of Chester, Deganwy fell without much of a fight. Llewelyn falling back to the relative safety of the mountains.

Seeking terms soon after, all Welsh lands east of the River Conwy were to be forfeit. Yet in a remarkable comeback, as soon as the English left to deal with matters closer to home and in France, Llewelyn was back. This time in alliance with most of the other Welsh kings.

As always, he picked his moment well, for soon enough all out war broke out in England between John and his barons, ultimately culminating in the king having to sign the Magna Carta in 1215, which guaranteed the rights of his lordly retainers and theoretically somewhat curbed the power of the king.

Llewelyn was there of course, having sided with the alliance against the tyrant king, and by 1216, in all but name, he was the king of all Wales. Able to portion out lands to nobles in the kingdoms far outside his traditional borders, acting as an overlord of all.

After John’s death, Llewelyn concluded a treaty with the boy king Henry III, though peace with England was all but assured due to the uncertainties attached with an infant ruler. The Welsh Prince was free to play his hand.

In the realms of the Norman marcher lords in the south-central hill country many a Welsh knight was crafted for war, and Llewelyn’s reputation grew and grew as he became more embroiled in the perenial wars there, sometimes allying with marcher lords, sometimes with other welsh rulers. Whichever suited his schemes best.

Finally by 1234 a true peace was declared, and for the last 6 years of his reign, having been named ‘Prince of Wales' in 1228, an honorific position as befitted the elder statesman he now was, he ruled over a truly peaceful land.

Almost immediately after his death however, as Dafyd ap Llewelyn attempted to solidify his new kingdom, Henry III was back at Deganway. The boy king was now a man.

This time he seized the castle for good, undertaking an extensive reconstruction scheme, spending a fortune in the process. When the castle was destroyed for good in 1263, left in the ruinous state we see today, it wasn’t the English that did it.

When Llewelyn the Last, a prolific castle builder himself, and every bit the match of his namesake grandfather, came here in the 1260s the place had become a symbol of English power. A revival seemed to be on the cards, but unfortunately for this Llewelyn, his adversary was one of the greatest kings the English ever had.

For before Edward Longshanks waged his wars against the Scots, earning teh title the Hammer of the Scots in the process, it was to Wales that he came to wet his teeth. When he was finally hounded into submission, there would be no mercy. Llewelyn The Last was taken to the Tower of London. He was hanged, drawn and quartered as a traitor.

Opting to leave the Welsh fortress at Deganwy in ruins forever more, Longshanks had a new castle thrown up using all the finest technology of the time. Conwy Castle remains as a constant reminder of that war torn age. It would be seven hundred years before the Welsh would win any sort of independence once more.

If you enjoyed this article here’s a video I made about early medieval Britain:-

While I dearly love your articles and the information contained within, you need an editor for spelling and grammatical errors. There aren’t too many, but I believe that your writing would be enhanced if you took this step.

Thank you for your stellar explorations that you share with us. I learn so much by your articles and videos. Incredible