Little remains now of the mighty Buddhas that once stood at Bamiyan.

Shadows, dust and colossal empty crevices where two of the great wonders of antiquity once stood. Fragmentary piles of rubble collected and catalogued by UNESCO World Heritage Organisation, and memories.

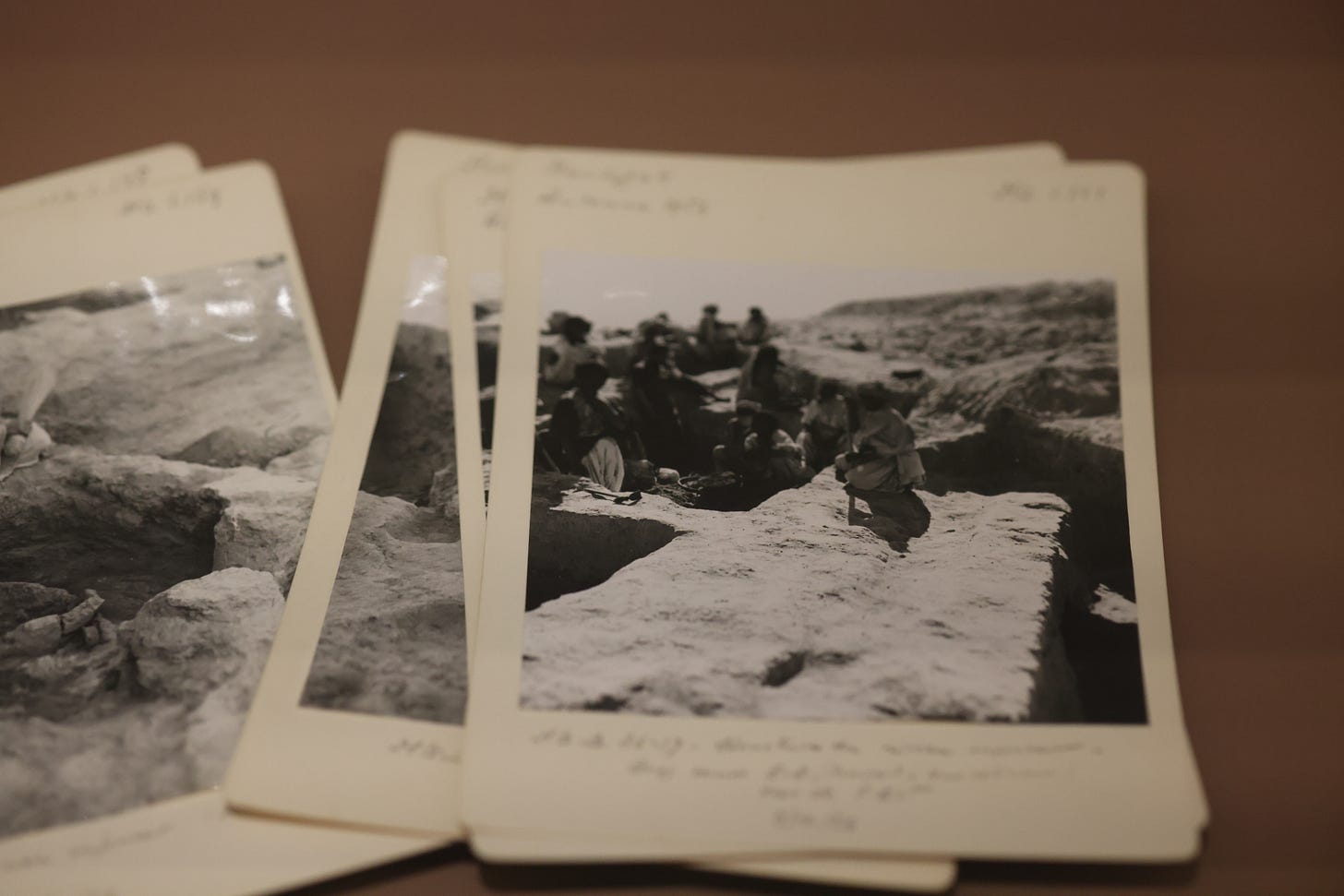

Last Winter my wife and I visited Paris’ Guimet Museum in search of the incredible prehistoric past of Afghanistan housed there after close to a century of collaborative effort between the French archaeological expedition and eager generations of Afghan scholars.

In the closing days of 2022 within those carefully curated halls, in the basement to be precise, an exhibition had been put on, displaying some of the prehistoric antiquities and photographs that remain of that golden age of Afghan archaeology. Taking us on a trip back in time to the ancient past of that most steadfastly isolated of Central Asian countries.

Far from a peripheral land, two thousand years ago Bamiyan had been at the very forefront in the exportation of goods and ideas all across the known world. For hundreds of years these remote Hindu Kush valleys acting as a cultural melting pot of ideas and peoples and a global centre of Indian Buddhism.

Only a little further north on the banks of the Oxus River the teachings of the Buddha were first carried into China, where they would leave a pivotal and lasting impression still very much felt today. The religion later moving back into India from there when it eventually died out in its place of birth.

The Bamiyan basin also acted as an excellent stopping off point for secular travellers; camel trains and wanderers heading along the well-trodden Silk Roads from the west. For back in that direction in those days stood the mighty superpowers of Persia and Greece. Two sprawling empires which would also leave lasting impressions on ancient Afghanistan.

It was from the north in fact that some of the most visible influence would come. For it was there in the land of Bactria that Alexander the Great had marched his armies to conquer in the Fourth Century BC. His generals and officers ultimately forging a Greco-Bactrian society which flourished for even longer than those Greek governorships organised in Persia. It was in this way that many ideas originating in India and Central Asia made their way to Europe, and Hellenistic togas made their way onto the Buddhas at Bamiyan.

Though Buddhism itself, for reasons still little understood, did not spread westwards into the Sassanian or Roman empires, Bamiyan, at a crossroads between India, China, Bactria and Persia stood in an excellent position to receive influences from all of these far-flung lands. Blossoming into a flourishing caravansary, trading post and spiritual refuge, regularly visited by devout Indians and Chinese on pilgrimage as well as mercantile Sogdians, Persians and no doubt, Greeks.

And in this multicultural land artistic matters were taken very seriously.

First came the cave systems. The cliffside here having been hollowed out and dug for thousands of years, creating an elaborate complex of interconnected tunnels and rooms stretching deep into the bedrock, walls coated by wonderfully elaborate and colourful murals depicting the stories and teachings of the people who flourished here from around the Second Century AD. Ultimately close to a thousand such rooms were hollowed out, almost every surface coated in the colourful artwork of those bygone days.

Next came the Buddhas themselves. Probably begun some time in the Fifth or Sixth Centuries AD when the Hephthalite White Hunnic steppe-empire ruled over Bamiyan. The statues are truly remarkable achievements. At a colossal 114 and 165 feet respectively they were carved by hand directly out of the sandstone cliff face. Perhaps most moving of all, those individuals who first conceived of and began the work would never see it finished, taking as much as a century to complete. Secular rulers and generations ebbing and flowing as the celestial message of the Buddha remained.

A complete departure from pre-existing sculptural traditions in the area, some scholars like Takayasu Higuchi see this new concept of colossal statues as an import from the west, from places like Egypt where the vast effigies of Rameses II still stood guard as they had for close to two thousand years. The concept perhaps being transmitted by an individual or group who made the journey there and back to the distant Nile.

And so it was. Whatever their origin, the work was eventually completed. Bamiyan continued to flourish, seemingly protected from the goings on in the wider world.

In 827 AD Korean Monk Hui-Chao came this way, writing that the king of Bamiyan was still Buddhist at that time.

By the Eleventh Century however, urged on by the feared outriders of Mahmud of Ghazni; mighty Turkic slave-general turned independent emperor, Islam first came to the valley.

Twelve times Mahmud had unleashed his horde onto the Indian subcontinent, waging an unceasing war against what he saw as a collection of idolatrous heathen states, and now firmly within his orbit, Bamiyan’s Buddhism would begin to ebb.

By the time Genghis Khan arrived in the Thirteenth Century, facing a defiant yet now mostly Muslim populace, he nevertheless took issue, as was usually the case. Turning his might on the caves themselves, where people still made their homes.

By the time the Pashtun king Abdur Rahman Khan conquered the region in 1893, the largest ethnic group in Bamiyan were the Hazaras, according to one theory they were at least in part the descendants of indigenous Turkic people and the warriors of Genghis Khan.

Though already firmly Muslim for hundreds of years, in a foreshadowing of what was to come a century later, many of the previously independent people of Hazarajat were rounded up and carted off to a life of virtual slavery. Forced to become indentured servants in the cities, serfs tied to the land in the countryside. For the Hazara are Shia, now living in a largely Sunni nation. Seen as beyond the pale of true Islam, their independence was stamped out, their mosques destroyed.

And yet soon enough cooler heads had prevailed and bridges were gapped. For a time the fledgling young nation of Afghanistan forged by those Nineteenth Century Pashtuns had flourished. Economic prosperity going hand in hand however with western culture, a situation hard line conservatives could never quite come to terms with. Underneath the surface ethnic and sectarian divisions continued to boil. From the outside, covetous foreign powers moved pieces on the board.

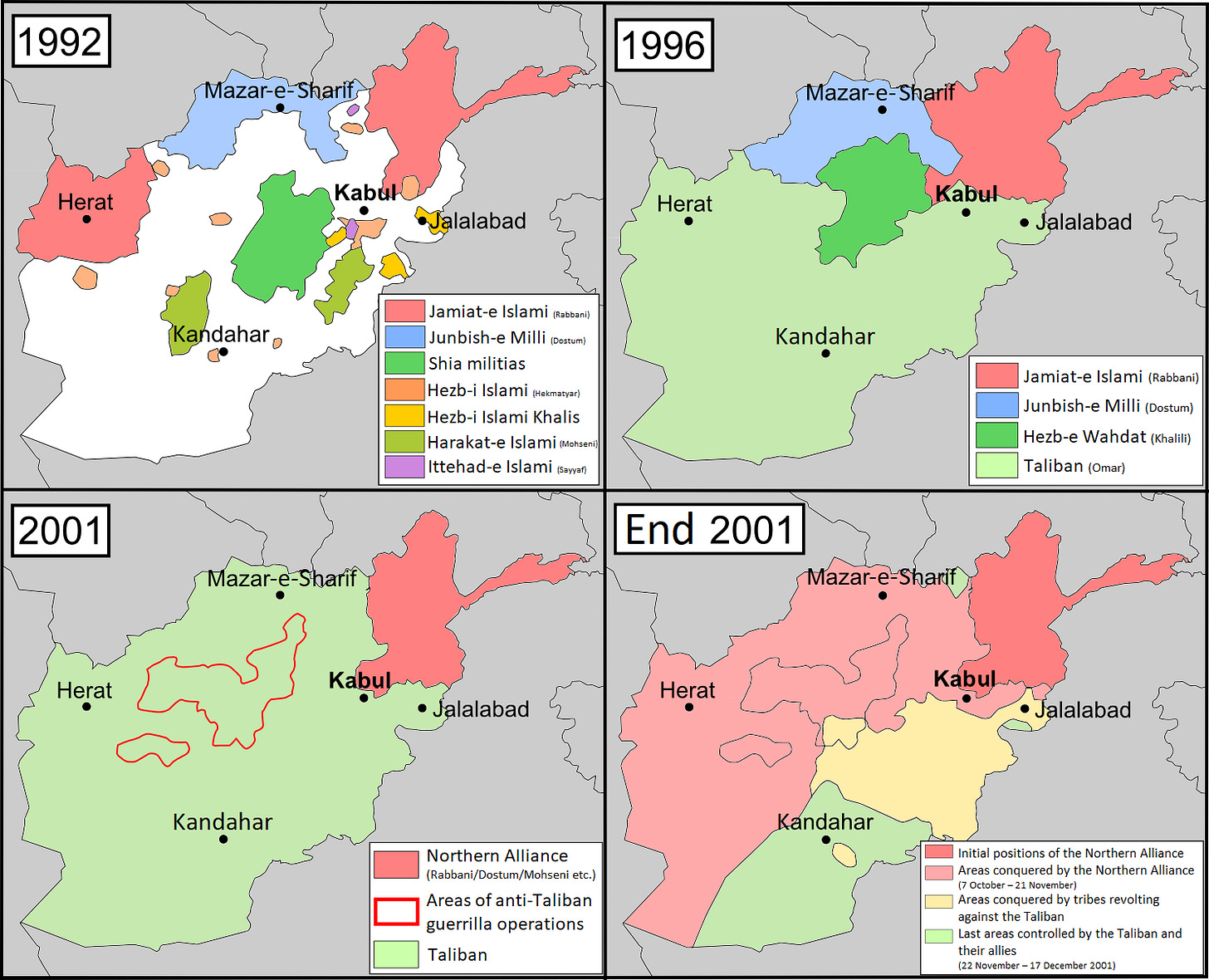

By the time the Taliban came to power in 1996, forging a fragile and brutally strict unity out of the various descendant factions of the Mujahadeen still fighting since the Russian invasion of the 1980s, the country had been ravaged by war for over twenty years. According to one report one in five children then being born in a refugee camp.

A year later the Hazaras of Bamiyan, long time sectarian enemies of the majority Pashtuns, were hemmed in. Out of the three or four million now surrounded by the encroaching Taliban army, one million stood at very real risk of starvation, and worse if the Taliban managed to get through. All relief attempts by the UN were blocked. Hunger now being used as a weapon for the first time in the twenty year conflict.

Far from being a backward mountain people as their sectarian enemies liked to portray them, many of the Hazaras present had recently fled Kabul after the Taliban takeover. Numbering university professors amongst their ranks, teachers and other professionals dressed in western clothing, harbouring at least some western ideals. Forced back to their ancestral lands now due to the war ravaging the nation. Now all alike sheltered in the caves in the shadow of the Bamiyan Buddhas.

With few allies to call on, the Hazaras had no choice but to rely on their co-religionists in Shi’ite Iran, who began flying in military supplies and vital food convoys. Soon enough Russia got involved too. Prompting the Taliban to successfully persuade Pakistan and Saudi Arabia to send them aid. The stage was set for a new ‘Great Game’.

Yet far from a united front, many factions existed within the Hazara, made up of millions of individuals with vastly differing political and social ideas, and that winter, hemmed in on all sides, the Taliban sat back and watched the Hazara tear themselves apart.

By August 1998 when the city of Mazar-i-sharif finally fell to the Taliban advance, many of the Hazara’s worst fears were confirmed when the violence boiled over into full on ethnic cleansing. Taliban soldiers driving around in pick up trucks indiscriminately shooting at anything and everyone that moved, ostensibly only targeting Hazara but also killing many others caught up in the fury. And soon enough, the violence spilled over into Bamiyan too. Anywhere between five and twenty thousand people being indiscriminately massacred.

As 200,000 revolutionary guards began manoeuvres just over the Iranian border, Iran-Pakistan relations hit an all time low. The conflict now threatening to drag in all of the surrounding powers into far more than a mere proxy battle. And somewhere amidst the chaos rockets were fired at the groin of the smaller of the Bamiyan buddhas; dynamite placed at its feet. Having survived the wrath of Genghis Khan, many of the cave frescoes now finally met their end.

In April 1999 Bamiyan changed hands again. Hope remained for the Buddhas. But by the start of 2001 the entire area found itself under Taliban occupation once more, now dominating the majority of the country besides the far north still held by the Northern Alliance.

The retribution of the Taliban would be harsh.

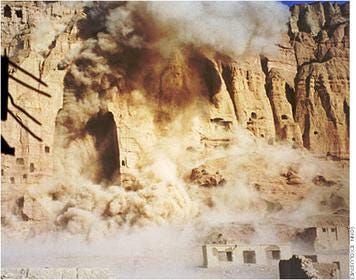

In February 2001 Mullah Mohamed Omar issued an edict from Kabul. On the grounds of their alleged idolatrous nature and potential to be used as objects of heathen worship, the Buddhas at Bamiyan would not be suffered to exist.

Far from the first attempt to destroy the mighty edifices, in 1646 the future Mughal emperor of India, Aurangzeb had one of his canons fire at the foot of the larger of the Buddhas, destroying part of its legs. The hands too had later been broken off by other zealous passersby. In truth they’d been under steady attack for more than a thousand years, kept intact by their sheer size. But by 2001 all the might of the modern world could not be stopped.

Between February and March 2001, not just the colossal Buddas, but a systemic obliteration of the entire cultural heritage of Bamiyan was carried out. By that time some fifty caves with frescos still survived, albeit desecrated over the years with faces carved out, but now they would entirely be destroyed. Because this time it would be different. This time the Taliban had demolition experts with them.

There are many eyewitnesses left to bear witness to the terrible events that followed. Local villagers were rounded up by gunpoint and forced to participate. Perhaps most damning of all, many of those carrying the guns were not even Afghans. Notably a large number of Arabs under Osama Bin Laden having operated in the country since the days of the Russian invasion, Pakistani, Chechen, Sudanese, Filipino, Kashmiri and Chinese jihadists further swelling their ranks. The latest in a long line of foreign aggressors to wage war in that valley near the roof of the world.

Drilling holes into the rock, five or six feet deep, the foreign soldiers stuffed the crevices with vast amounts of dynamite.

Long the peaceful guardians of this historically pivotal crossroads and arguably the jewel in the crown of Afghanistan’s cultural heritage, those wonders of the world that had taken one hundred years to build, were obliterated in seconds.

Those forced to participate saw their culture fall through their fingers like grains of sand on that day. All the pressure of influential world leaders and international cultural organisations alike ultimately powerless to stop an unrecognised government intent on eradicating its own Pre-Islamic heritage.

By the end of the year the September 11th attacks had kick-started yet another invasion of Afghanistan, this time by the Americans, and the Bamiyan region was liberated from the Taliban once more.

For the Buddhas though, and for much of the rest of Afghan archaeology, it was already too late. The events of February and March being just the final culmination of twelve years of systematic looting and devastation of Pre-Islamic sites, leaving Afghanistan bereft of its once world class array of Greek, Buddhist, Mongol and even early Islamic history.

It wasn’t long before chunks of the Buddhas began showing up for sale in Pakistani bazaars, reportedly being sold as paperweights. And though huge pieces still remain at the base of the now empty alcoves, painstakingly collected by UNESCO and local people, due to the sheer costs involved, and with still vast amounts of infrastructure like bridges and schools still derelict and broken in the region, the decision has been made not to rebuild.

Today the empty alcoves are left as a reminder of just how fragile a society can be. How easily culture can be lost.

It’s thought that as much as 70% of Afghanistan’s excavated heritage has been destroyed over the last three or four decades. Either destroyed outright or disappearing into the collections of private buyers on the black market.

One notable occasion taking place amidst the civil war in 1993 when a rocket attack tore through the Kabul Archaeological Museum, resulting in widespread looting and the need to re-excavate the surviving museum collection.

It’s difficult not to be moved as we walk the corridors of the Guimet Museum, vast panorama of Bamiyan splayed on the basement walls ahead of us.

Only a tiny handful of items excavated from Afghanistan have made their way to the display cabinets here. Truth be told, there isn’t much to see. The permanent Indus Valley Civilisation wing upstairs is closed for refurbishment and there isn’t a permanent Afghanistan exhibition as I’d hoped. Most people being more interested in China, Japan & Cambodia it seems. All I can hope for is that somewhere in the back rooms some of the excavated material from Afghanistan still remains.

—

When the French Expedition to Afghanistan first began in September 1922, almost exactly a century removed from my visit to the Guimet, the world certainly seems to have been a simpler place. A brief moment of calm amidst the violent upheavals of the Twentieth Century.

The French had soon been followed by Italians, Americans, Japanese, British, Indians, Soviets and most importantly, Afghans who’d conducted their own digs in the mid 1960s.

These were excavations that extended Afghan history back thousands of years to the distant Early Bronze Age of the Third Millennium BC, and even earlier, uncovering a dizzying array of sites inhabited down the long centuries since.

Yet more multitudes are still waiting to be dug, having only been preliminarily surveyed or simply marked on a map. Their secrets thankfully still safe under the ground for future generations to behold.

Perhaps most importantly, due to the uniqueness of the opportunity to reveal such a rich, previously un-archaeologically unexplored land, these digs were carried out with the utmost scientific vigour, highlighting the very latest cutting edge techniques each country had to offer.

One of the most impressive and astonishing digs of all was conducted by the French in the 1950s. For in the mountains north of Kandahar the unthinkable had happened. A mighty city of the ancient world had been revealed. Contemporary of Ancient Sumeria and the Indus Valley Civilization. During a time when nothing else like it existed in the vast majority of the world.

That mist-shrouded prehistoric metropolis five thousand years removed from today should be a wonder of the world, and yet it remains barely even known. Its very existence an affront to conservative hard-liners in the state it now finds itself in.

—

A handful of Early Bronze Age sealstones were on display at the Guimet when I visited, similar to ones I’ve seen over a wide area from Greece to the Arabian Sea. But of the rest of the finds, of the elaborate goblets, the pottery and the statues, I know not. There is no one left to speak for Mundigak today.

In order to delve deeper into the story, and to find those who did once speak for that vaunted city of old we must go back just a single generation from the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas to the halcyon days of 1955…

Don’t forget to sign up with your email so you can be updated when the next episode on Mundigak is released (It’s a goodun)

If you want some more History Time then here’s a video I made earlier:-

The destruction of the Buddhas always makes me so sad; I saw a documentary a few years back on YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VXXmcGirPMA : 'David Adams was the last Westerner to exhaustively film them before they were blown up in 2001'. So glad there's footage of them like this from before they were destroyed