It was early morning when I got to Aokigahara Forest. Tree-roots and moss grasping all in their silent embrace. A thin layer of mist still lying low over Lake Fuji before the sun had a chance to burn it away, the rich dark soil and bed of leaves beneath my feet seeming to dampen all but the nearest of sounds.

All the while, the mountain above remained strangely clear, its gargantuan peak completely dominating the skyline when I’d gone up to the observation deck at my lakeside hotel before breakfast. Enjoying there my first up close meeting with that snow peaked monster at the heart of Japanese national identity.

Only later did I learn that this isn’t always so. The seemingly omnipotent Fuji-San by no means always revealing itself to passers by. Having already seen it clearly from the plane as I came in to land at Tokyo a few days earlier and then over and over again aboard the sprawling train network of the central highlands, it never even begins to get old. There’s just something special about that mountain. Always has been.

At 3776 metres, it is the tallest in all Japan. A sacred titan of gods and mortals standing sentinel down the centuries. Since its fiery creation some 100,000 years ago, when the heavens stretched their fingers down to the earthly realm, it has remained a muse to poets, a beacon to pilgrims, and now, the heart of a nation.

Once considered a god in itself, for millennia the silent giant has watched the march of history unfold around it. From the first fires kindled and pots created by Jomon hands as much as 15,000 years ago to the samurai who sought solace on its slopes in the last millennium. From the Shinto & Buddhist monks who traced its ridges in search of enlightenment, to the artists who immortalised its form in ink and woodblock, Fuji has born witness to the ceaseless movements of time. Today it is memory itself, carved in rock and snow. And it is still alive. All the meteorologists agree - its last eruption in 1707 will soon be followed by another.

But the mountains shadow is long, and beneath its towering form lies another realm entirely. An emerald labyrinth of gnarled roots and trees, where the wind is hushed to silence and the past seems to linger like an icy breath of air.

Also known as Jukai, the ‘Sea of Trees’, the forest of Aokigahara is many things. To interested travellers like myself it is a cradle of folklore, a place intrinsically linked to the story of the Japanese people. To others, one of whom I would meet that day, it is a place of darkness, and death - a kind of danger tourism hotspot. To yet more it is a refuge of solitude within only a few hours of the dizzying bedlam of the largest metropolitan area on earth. And finally, to a solitary few, it is a place where life meets a quiet end.

For there is a darkness beneath this ancient canopy, Aside from the popular tourist caves that can be found throughout and the many easy bus routes from the idyllic lake-side resorts like Shoji and Fuji, Aogokaraha has another name. The suicide forest. A place where men and women from all over Japan have come for centuries to slip silently away and rest eternal amidst the trees.

As far as Japanese folklorists are concerned, as well as many followers of the traditional Shinto faith of the islands - an immensely old religion - Aokigahara is far more than just a forest. It is a liminal place where life and death entwine. Past and present, legend and reality coming together in the shadow of a leviathan of the elder days. For those of this persuasion who dare to enter, it is a place that never truly lets go.

As I entered the forest that day, following the carefully laid out pathways and meeting many friendly faces along the way, I couldn’t help but think of the old stories of the place. Of the Yurei - wandering spirits trapped between our world and the next, drawn to the darkness in Aogikahara’s depths.

Like most traditional folklores around the world, though few survive anywhere near as completely as a place like Japan, tales of demons and spirits lurking in the trees of wilderness areas such as this are common. Calling out in the night and echoing through the labyrinth of moss and stone to lead travellers astray. But there was more to this forest, for in times of famine and hardship, it is said that people, old or weak or in some way perceived as a burden on the rest, would go to the forest to die, sometimes leaving their souls behind in its embrace. If you are of this way of thinking, then even today as modern roads pass through the vast expanse of green, the spirits of the dead remain. Perhaps adding their collective essences and energy to the woodland. Though those who were angry when they died or had unfinished business remain to haunt the place as dangerous Yurei.

But just as there is death there is life here too. The 35km area of Aogikahara is considered one of the most significant biodiversity hotspots in all of Japan in fact, with several species of rare butterfly and other animals found in abundance more than anywhere else in the central regions. Though you wouldn't know it due to the all pervading silence, vast amounts of animal species are to be found, including Asiatic Black Bears, Raccoon Dogs and Wild Boar. This is not surprising at all, for the ground I walk on as I enter the forest is clearly of volcanic rock. As much as this is a place of endings, it is also a place of rebirth, not just in the Buddhist conception of rejoining the cycle of existence after death, but in biology. For the entire forest has grown up on top of a lava bed of over a thousand years before.

It was during that eruption of 864 to 866, recorded in the Nihon Sandai Jitsuroku that the lakes of Motosu, Shoji and Saiko were formed, when the vast lava flow separated a larger lake. Lava having spewed forth down into the lake at its base, transforming the landscape into a network of chasms and caves formed deep below the surface, changing the landscape and surely the National psyche of the people around it too. Valleys were filled in, life eradicated. What a sight it must have been. The impact of the eruption being so severe that a shrine at Asama was established in the foothills to ward off further eruptions. And yet, though the biggest eruption in recorded history, the immensely fertile new ground led to the forest we see today.

By the Twelfth Century, though the power of the volcano survived in memory, enough in itself to create a whole slew of myths and legends enacted in songs and dance and perhaps contribute to the dark reputation of the place, it was deemed stable enough for Satsudai Shonin to establish a temple on the very summit. Worshippers regularly climbing as part of the syncretic religion of mountain worship known as Shugendo, as is common in Japan, a mixture of Buddhism and more ancient ideas.

Even with strong winds above, as I wander in the woodland, it is particularly quiet. Amidst the silence I remember the supposedly strange characteristics of the place - magnets and watches not working properly for example. A quick check reveals these to be travellers tales. And though the place feels like many other forests I’ve been to, I can perceive an eerie, otherworldly feel.

The giant trees that have grown up so densely over the last thousand years sometimes making it feel like dusk even though it’s the middle of the day. The foliage and the volcanic earth consistently blanketing every sound. With no carefully maintained tourist paths in pre-modern times, the ground itself would seem booby trapped with roots that threaten to trip up or grab out at all but the most observant of wanderer.

But what of the forest before the eruption? Before the volcano destroyed the land, before newer trees and stories with them grew tall and thick, before their tangled limbs wove a barrier between worlds. Of course, this land was already ancient, and Fuji-San remembers.

Around 11,000 years ago, an earlier eruption had caused a vast amount of lava to form the entire west side of the mountain we see today, completely altering its image. This was an age when Japan’s first complex societies shaped clay with fire, painted their bodies with ochre and constructed impressive monuments on the landscape - hunting, gathering, creating art and wandering.

During that age we know now as the Jomon Period due to the elaborate knot-work on their ceramics, the forest was a place of awe and reverence. More connected to the land than later peoples, those first inhabitants of Japan must have known the mountain was restless. The land itself moulded by its breath.

For thousands of years, complex hunter gatherers of the Jomon Period didn’t just live but thrived all through the central highlands of Japan to the slopes of Fuji itself. In those days when the wild wood coated all the earth, the hunters enjoyed intimate connections with the world around them, playing music, creating art, and perhaps like some still do today, feeling a presence in every rustling leaf and shifting shadow. They carved strange patterns into stone, fired great masterpieces in clay and in what was once assumed to be a unique case for people living a hunter-gatherer lifestyle, came together to create mighty monumental architecture.

At the south western edge of the mountain one of their vast ceremonial sites can still be seen today. The settlement of Ōshika-Kubo, found when road works were being carried out in the 1990s unfortunately can’t be seen overground today but has nonetheless been investigated archaeologically. Dating to some 15 to 12,000 years ago, it is just one example of a complex society that spread over all of Japan for millennia. We don’t know for sure, but some facets of the Shinto religion may in fact stem all the way back from these wildly early people, still immensely popular in Japan today.

Finally by around 300 BC, everything would change. After tens of thousands of years of isolation, rice farming would arrive on the Japanese mainland. And almost immediately when this new and intensive way of creating food swept across the islands, wealth accumulation, elite rule and violence came with it.

This age, known as the Yayoi, most famously seen in the bronze bells that line museum shelves across the country, seems to be accompanied by a new Chinese style religion, way of life and population groups. Though no doubt some older Jomon ways survived too, ultimately merging to create Shinto.

It is in the period that follows, beginning in the first few centuries AD and only ending with the arrival of Buddhism by the Sixth Centiry, most famously known from its huge elite funerary monuments, that the Japan we know today has its roots. This was the age of the Kofun, a time of rising empires and warrior kings. When great tumuli - earthen pyramids - were built to house the mighty in death. The rulers and elite of this land, their bodies adorned with bronze and silk, were buried in chambers that in many cases, not being allowed to be investigated, still slumber beneath the soil.

If the Kofun had a presence around Fuji, Aogikara likely then being a place of reverence, and perhaps a border even then between the living and the lost, it lies buried deep. Perhaps those kings and queens of old still drift as unseen sentinels amidst the trees.

By the time Buddhism arrived in Japan in the Fifth and Sixth centuries AD, many of the characteristics we associate with the later age of the Samurai were already in place. A quasi-feudal system of haves and have-nots and the institution of the Emperor among them. One such facet of Japanese faith seeming to long predate the arrival of Buddhism is the Obon Festival, first recorded as having been celebrated under the empress Suiko (592-628).

Still celebrated every year in August all these centuries later, the original festival likely took place twice a year, in Spring and Autumn, always on the night of a full moon. Intrinsically linked to ancestor worship, not too dissimilar perhaps to ancient religions all over the world, the intention of the celebrations was to beckon the deceased home to their family homes to pay homage. In order to do so families will traditionally return to the lands of their ancestors, cleaning the household altars while there and taking part in a dance known as Bon Odori.

According to the old religion, when a person dies, their soul, or reikon leaves the body to enter a kind of purgatory. If the deceased died a good death and the proper funerary rites are performed they may rise to join the exalted ranks of the ancestors, watching over their descendants and returning each year during the Obon festival to receive thanks. If a person suffers a violent or sudden end however, or has strong unresolved emotions like anger, a desire for vengeance, jealousy, intense sadness and even love, or even if the proper funerary rites are not satisfactorily performed, the reikon will not be freed from its earthly cage, nor allowed back into the cycle of reincarnation. Transforming instead into a Yurei. A dangerous spirit or ghost. These Yurei are often associated with a particular place, and of all these places, the most yurei haunted of all, is none other than Aokigahara Forest.

Sometimes, the more harshly an individual was treated in life, or the lower the social rank they held, such as Oiwa in Yatsuya Kaidan, or other figures of Japanese literature, will lead to the return of an especially powerful Yurei. If the proper rituals and or emotional conflict suffered by the individual are never resolved, the spirit will remain on earth forever more, lashing out at the mortal realm and leading to the especially morbid reputations of Yurei haunted landscapes like Aokigahara Forest.

While waiting for the bus back to town, shattering my perceptions of Japan by being an hour late, I met a young metalhead from Taiwan. He’d studied Japan at university he’d told me, links apparently remaining strong between these two East Asian allies of the United States. I told him how I’d read of the folklore of Jukai, he told me he’d done the same. But he was there for something more he said. He’d left the paths, to go searching for a body. No doubt many other visitors do the same. The grim reality is that Aokigahara is the second most popular suicide destination in the world, only the Golden Gate Bridge being more popular.

Though as we have seen, the forest has over a thousand years of recorded history to draw from, much of its popularity in the last century in fact stems from a single work of fiction. A 1960 novel by Seicho Matsumoto by the name of Nami no Tō - Tower Of Waves. Though the nihilistic masterpiece of post-war malaise mostly takes place in Tokyo, its finale, where its beautiful heroin takes her own life, is of course in Aokigahara. Turned into a movie within a year of its release and followed by new adaptations every decade since, Tower of Waves was an absolute phenomenon in its day. Unfortunately, hundreds of bodies recovered from the forest have been found with the book on their person in the decades since. Other wildly popular books in Japan like Norwegian Wood by Haruki Murakami also contain suicide. Understandably, authorities in Japan stopped releasing figures of those who lose their lives in the forest a long time ago.

It isn’t that Japan is particularly rare in the world in its rates of self-inflicted death. The mythic concept of ubasute, where the infirm are left in a wild place to die, and shinju - lovers suicide, being similar to the Greek Tragedies and Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet for example. But the reasons that some go down this route remain very unlike those in the west. Imagine if the Greek tragedies had taken this concept alone and ran with it forever, with no Judeo-Christian values to condemn the killing of the self. The self-inflicted seppuku committed by samurai for example as well as the kamikaze pilots of World War Two are unlike anything seen in the west.

One argument is that the co-operative native of rice farming in East Asia leads ultimately to a collectivist culture in Japan and the areas of China and South East Asia where it predominates. By this reasoning, wheat and grain growing areas on the other hand tend to be more individualistic so can lead to individualistic cultures like Europe and United States.

Unlike in the west, In Japanese culture the self is deeply connected to the communal. Social mechanisms historically valorising rather than abhorring suicide as a worthy act if committed for the benefit of others.

From salary men who no longer wish to suffer the indignity of unemployment or who have made a grave mistake in business, to elderly folk wanting to remove their perceived burden on their descendants, innately hierarchical structures led by invisible networks of obligation and deference have traditionally acted to bind Japanese society by a code where self-inflicted death can be the ultimate heroic act.

All the way back in 1897 just as Japan was opening up to the wider world, sociologist Emile Durkheim investigated this concept, which he called ‘Altruistic Suicide’, finding it present in many cultures on Earth. From early legends where self immolation in particular was praised to the semi-legendary ubusate of the Eighteenth century where elderly or sick chose their own deaths to make way for the next generation, this tradition of self-sacrifice has verifiably existed within the Japanese psyche via myth and written works for centuries, perhaps even millennia, potentially being brought with the first rice farmers over two thousand years ago. With self-inflicted death even being framed positively as the removal of responsibility, even today through the lens of Japanese cinema, theatre and literature we can see these traditions personified when describing romantic acceptance of voluntary death. Quite simply it has become entwined with what it means to be Japanese.

In recent years however the forest has developed a particular reputation for the dark, with many locals apparently shunning the forest. Some even believing that merely entering the place can cause mental anguish that will ultimately lead to suicide if left unchecked. Arguing the negative energy of the many thousands who have died here to have infused with the trees to create especially dangerous Jukai.

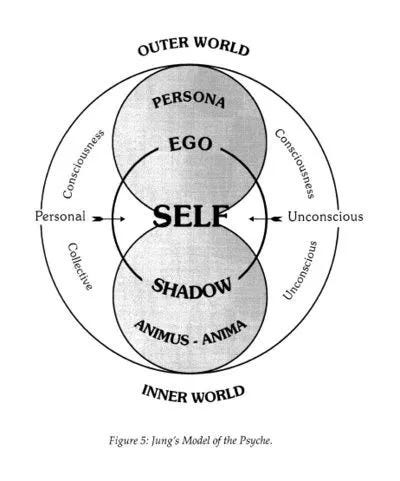

Today, the human brain is widely considered the most complex structure in the known universe. A machine for the creation of of meaning which neuroscientists still barely understand, it is no surprise that certain locations like the Aokogihara Forest seem to conjure up feelings of malevolence for large numbers of people. Many locations the world over having developed either positive or negative reputations down the centuries, very often seeming to exist outside the realm of the human mind. Back in the early 20th century concerns such as these inspired pioneering psychoanalyst Carl Jung to ask the question - does a landscape have memory? Or alternatively - does a landscape have a soul? Linking his question to the concept of the collective unconscious and Sigmund Freud’s idea of ‘Archaic remnants’ left over in human groups, his resounding answer was yes, certain places may become imbued with a sense of soulfulness due to the intense meanings placed on them by human cultures.

The concept of a ‘sacred landscape’ has become popular in academia in the last few decades. With investigations into how certain landscapes can influence human activities being undertaken in many disciplines. It has been argued that a sacred landscape is not simply what we see with our eyes, particularly for someone outside the cultural frame of reference, but a way of seeing with our mind. Ultimately this is the concept at the heart of the ancient Japanese Shinto faith. As well as most other animist religions all over earth - a kind of Shintoism once having been practiced by all humans, including my own ancestors in ancient Britain and Ireland. Absolutely everything was imbued with a spirit, some considerably more powerful than others.

Still worshipped at thousands of shrines today, though often left purposefully ambiguous, these ‘kami’ worshipped in Shinto can refer to animals, the souls of the dead, former emperors, forces of nature, landscape features, forests, people of particularly outstanding deeds and virtue, powerful gods and goddesses, like Ameraysi the sun goddess, the moon goddess Tsuyuyuomi, the storm god Susano, and vaunted ancestors. Shinto is a fascinating and particularly well developed insight into the ways ancient people throughout human history very likely viewed the world around them.

Having been added to many times over the centuries, particularly by Buddhism, the heart of Shinto is still intact, in particular the idea that upon death people can essentially be incorporated into the animist forces of nature. Many peoples all over the world still have their sacred mountains for example, places of numinous power, whether they realise this is the case or not. Originally they would likely have been seen as individual entities In Japan the relationship between these kami and natural places like mountains but also trees, rocks and waterfalls, designated as such by priests with traditional ropes and strips of paper has led to the establishment of thousands upon thousands of shrines, some wildly ancient, though anyone can put one up, and sometimes they do, particularly for lost loved ones. Creating symbiotic relationships between the shrine and the natural world. Some today are in built up environments but all originally would have been in a place of natural beauty. Transforming topographies to living graveyards.

If anywhere can hold memory or a soul as Jung ponders then, surely it is here in this most sacred of places in a land where the past never truly sleeps. To those of Shinto persuasion, already psychologically prepared to feel a certain way when they arrive, the forest is a powerful place indeed. Where the earth whispers. Where time slows to a breath and the wind carries voices long forgotten. Light and shadow weaving their endless dance amidst the murmurs of history, myth and the unseen world beyond.

As an outsider in the sea of trees I find not darkness, but peace. A place of stark beauty, of solitude and serenity. I stare upwards to the canopy, and venture forward into its depths.